Well, here we are two weeks later and it appears the “national” hockey media is still talking about Auston Matthews.

I mean, I know it’s Toronto but come on. Leafs fans really should change their little slogan to “Buds 24/7, 365.”

Anyway, just when I thought everyone had moved on, Matthews is back in the spotlight because now he’s allegedly feuding with Leafs coach Mike Babcock. But more on that later.

First, let’s recap how the mainstream media turned on Matthews during that Toronto-Boston series.

It all started with a 3-1 loss in Game 4 of the Leafs’ first round series against the Bruins. Matthews was a non-factor, but then so were the rest of his teammates. But what really burned the Toronto media was that Matthews wasn’t made available to the media following the game. So much so, that they were still harping on it a week later:

Jake Gardiner is a good kid. And huge kudos to him for facing the music and being accountable for the way he played. Auston Matthews hid in the training room after being invisible in Game 4.

— Ken Campbell (@THNKenCampbell) April 26, 2018

This led to one of the most incredible sequences I have ever seen on hockey twitter:

That’s right, folks. Elite hockey talents become better players by talking to the media!

I actually find this idea that facing your critics makes you a better as a person and in your chosen profession amazing coming from a group that can’t hit the block button fast enough at the slightest critique on twitter:

Yes, these are grown men that can’t handle a little push back on the internet getting apoplectic that a 20-year-old kid won’t come out and answer their trite questions with tired clichés.

Just to put a little context around this, two of the six forwards to win the Conn Smythe Trophy for playoff MVP didn’t get off to great starts their first couple of years in the playoffs either. Justin “Mr. Game 7” Williams went 1-5-6 in 17 games, while Henrik Zetterberg went 3-2-5 in 12 games. For context, is 5-2-7 in 13 playoff games. The point is, he’s just a kid and the fact the Leafs have to rely so much more on him is on the rest of the team, not him.

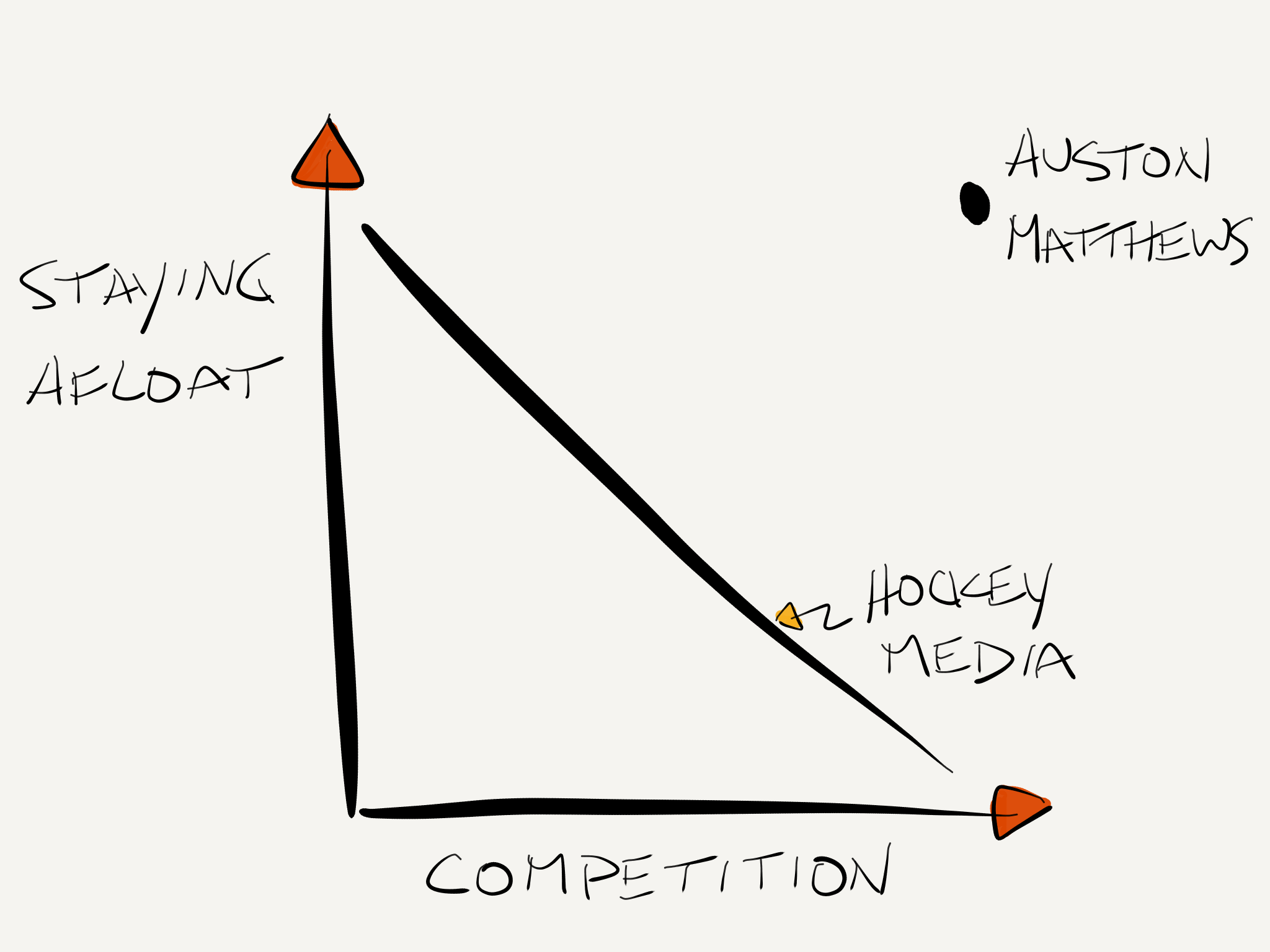

This brings us to the topic of competition.

Now, over the course of a season I’m not convinced that quality of competition varies enough between players that it has a large impact on overall results. But over a short period of time, especially a playoff series, who you’re playing against can, and often will, be much more drastic. Not only are you facing the same actual players over a series, as opposed to players of similar “quality” by whatever metric you’re using to describe that, but the line matching is much more extreme.*

Let’s take Brandon Sutter as an example, and we’ll look at competition a couple of different ways. First, here are a couple of charts showing how Sutter fared against every opposing forward in each game he played this year. In this case, we’ll assume that NHL coaches are good judges of overall player quality and allocate ice time based on that quality. So along the x-axis we have opponent quality by 5v5 TOI/GP.

That ice time can also be expressed as a % of total 5v5 TOI available. So for example a top line player getting 16 5v5 mins per game on a team that averages 48 5v5 mins would be expected to be on the ice 16/48 = 33% of the time at 5v5. And if there was no line matching, and ice time was assigned purely randomly, this means that if Brandon Sutter played 15 5v5 minutes against this player’s team, we would expect them to be matched up 33% of the time, or 5 minutes. If we compare the actual head-to-head TOI with this expected value, we can get an indication or how much more or less Sutter played against this player than if the ice time was purely random, i.e. how much line matching or sheltering was going on. That’s what we have on the y-axis.

The chart on the right shows us that Sutter was indeed used to match up against higher TOI opposition over the course of the season (the vertical lines roughly represent the split between 3rd/4th line TOI and 1st/2nd line TOI). The chart on the left shows that for the most part, the players he faced did better when he was on the ice against them than they did overall, i.e. they had a better shot attempt (Corsi) differential vs. Sutter than their average. And the higher the opponent’s TOI, the worse he did, in general.

The other way to look at player quality is by shot attempt differential, which we can see in the two charts below.

Here, the y-axis remains the same so that we can see how much more or less Sutter faced the opponent compared to a random deployment, but along the x-axis we now plot those opponents by their shot attempt differential. Here the vertical lines are at +/- 5 shot attempt differential per 60 mins, which again are roughly the break points between 3rd/4th line performance, and 1st/2nd line performance.

So when looking at Sutter’s competition in terms of shot attempt differential, we can see that with that as a measure of quality, Sutter did not really face particularly tougher opposition that we might expect. And in terms of performance, he was generally below expectations across all ranges of opponents.

With the explanation out of the way, let’s look at Auston Matthews’ competition in that first round series against the Bruins. Here he is against the Bruins forwards:

The first thing to notice here is that Boston did not do much to match specific “shut-down” forwards against Mattews’ line. The competition was basically what you would expect with random deployment. And in terms of on-ice performance, while Matthews was under water against Bergeron and Marchand, his line wasn’t dominated any more than you would expect up against them. But he more than made up for that against the rest of the Bruins lineup and wound up above water overall.

It’s when you look at Mathews’ matchups against the Bruins defensemen that you can really see how Boston was playing against him. Most coaches tend to focus more on matching defensemen against the opposing top lines, and that’s certainly what was happening here:

Matthews was overwhelmingly matched up against Chara and McAvoy and did very well against that pair.

So sure, Matthews was unlucky in terms of goal scoring, and ultimately that is the point of playing hockey games. That is the thing that gets you to the next round. But he was also matched up against the Bruins’ top defensive pair.

Compare that to Tyler Bozak, who was able to feast on the bottom end of Boston’s lineup, whether it was the defensive pairs of the forward matchups:

And compare also to Patrick Marleau, who was pretty heavily matched against Bergeron, Marchand, and Pastrnak but didn’t do nearly as all in terms of holding them to their expected shot attempt differentials:

And he had the luxury of staying away from from the top defensive pair:

But hey, he scored four goals and presumably answered the media’s questions, so it’s all good.

The point is this, process wise, Matthews did ok given the competition he faced. Could the results have been better? Sure, if more of those scoring chances wound up in the back of the net, no one would still be talking about this. And maybe if he had a chance to play a bit more, some of those chances would eventually start going in. But Babcock was all about “balance and depth” so Matthews didn’t get the ice time an elite player might usually get:

#Leafs head coach Mike Babcock was asked on @OverDrive1050 why Auston Matthews doesn't get as much ice time as stars like Connor McDavid or Aleksander Barkov. This was Babcock's response.

Full interview here: https://t.co/Aq0dZtq3xS pic.twitter.com/ChwESOyOlH

— OverDrive 1050 (@OverDrive1050) April 27, 2018

And hey, maybe he’s right. As I said above, Matthews is still just a kid.

Unfortunately, some in the Toronto media don’t seem willing to accept or even acknowledge that.