Lockout considerations

Speaking with lawyers is often a good way to get to the root of the argument.

Earlier this week, some interesting concepts emerged from a recent conversation I had with a pair of lawyers I know in Toronto. With the lockout beginning officially on Saturday night at 11:59 PM EST, I figured I’d share four points of particular interest. Check them out after the jump.

Making money is number one

At the heart of the current lockout is – surprise, surprise – the almighty bottom-line. Consider this: Rogers and Bell didn’t team up to buy MLSE because they think it makes them look cool – they bought the sports conglomerate because it’s massively profitable, driven as much by the Maple Leafs as anything. When the owners lock out the players, they don’t generate nearly as much revenue. NHL owners will still split 200 million from NBC for the TV deal, and they won’t be paying out any money in player salaries, but still: no revenue, no profit.

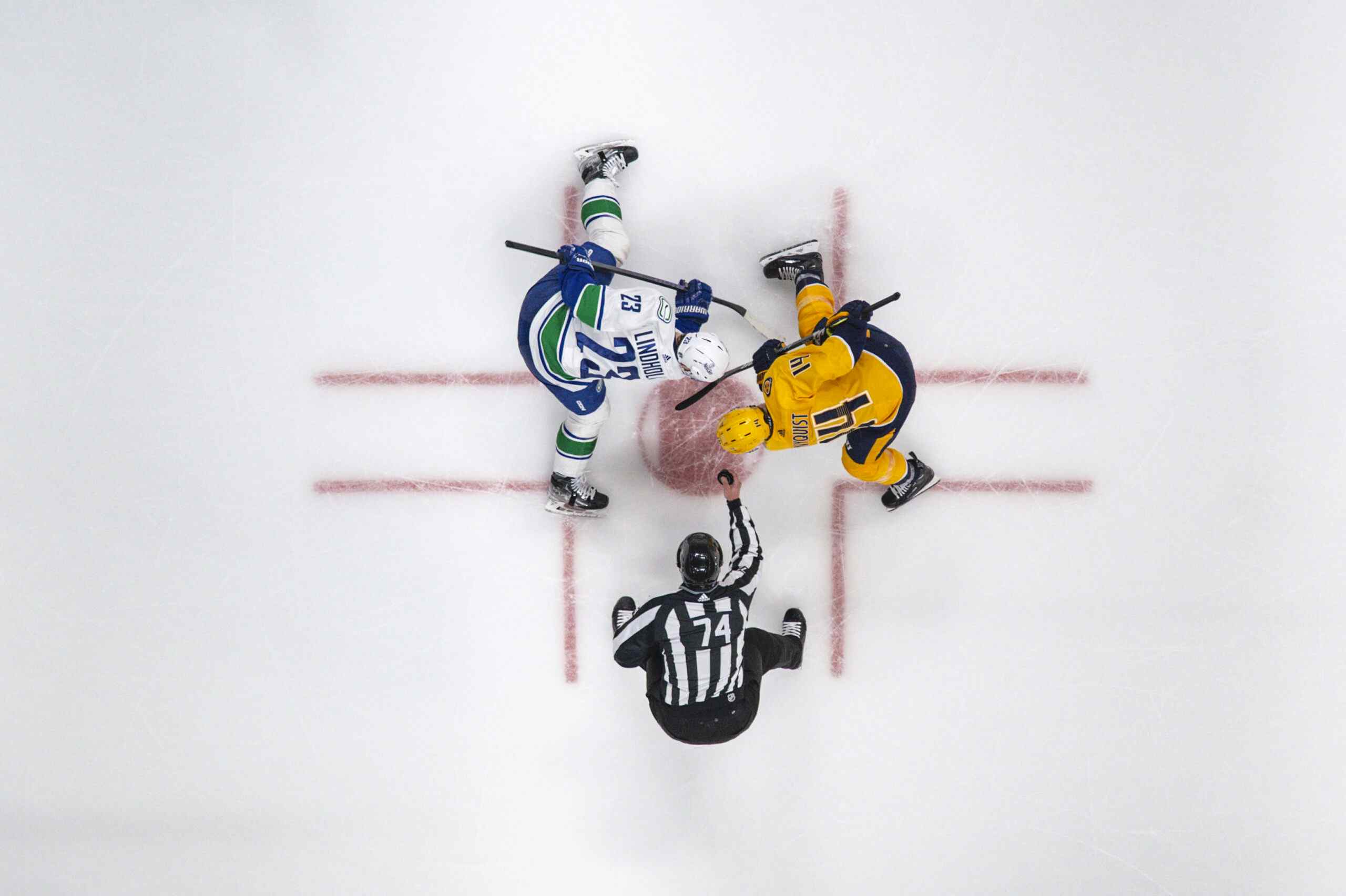

The Aquilinis will probably look at it in a similar way, even if they derive more "psychic benefit" from owning the Canucks, than two media conglomerates do from owning the Leafs. So while Canucks ownership spends a lot of money on their team simply because they want to win, it helps that the Canucks are also highly profitable.

The fact remains, that if the doors to the arenas are closed, the big boys in Toronto, New York, Montreal, Philadelphia and Vancouver won’t be raking in the cash. These sorts of teams are the NHL’s economic engines, and no revenues from them is bad for the league as a whole.

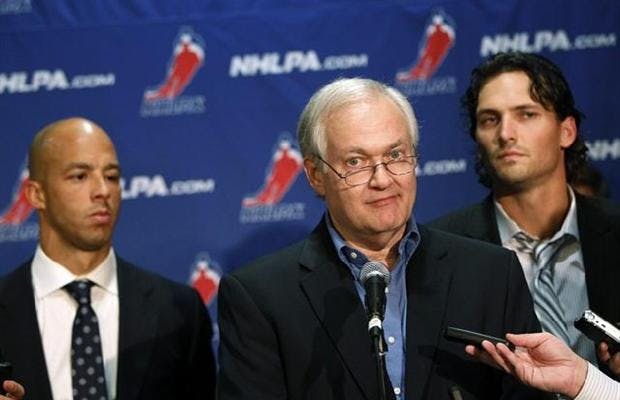

What the NHLPA does

One idea that has been bandied about is the continued viability of the NHLPA. It could be argued that the NHLPA actually serves the owners’ purposes as much as anything. Having a CBA actually controls the players’ negotiating power and makes the owners’ labour costs stable. If there’s no labour-law relationship, then it’s a whole different ballgame. Players would be negotiating each contract on its own terms, and there wouldn’t be as much uniformity of provisions.

Top-end players would still get paid plenty, and with the parameters laid out under the former CBA arrangement fresh in everyone’s mind, it’s fair to expect that players would continue to ask for benefits and clauses similar to those that presently exist.

However, as we get further and further away from the top of the skill-pay ladder, players would probably find their salaries being driven down. As Tyler Dellow has shown at mc79hockey.com, players up and down the lineup have benefitted from the perceived scarcity of talented second and third line players. Players in those ranges have effectively been ‘slotted’ in their pay.

It’s the players on the fourth line who most benefit from having a CBA. With no CBA, there would be no minimum salary, meaning the jobs of guys like Tanner Glass would probably no longer be valued at $1,100,000. Instead those jobs might fall to 19-year-olds who might be willing to play for $200,000 (or maybe even less).

Having a CBA has been beneficial for every NHL player because it has clearly defined their value. It has been very beneficial for owners for the exact same reason. The thing the owners can’t stand, however, is the inflationary pressures that inevitably exist in any system – the salary escalation created by the scarcity of talent. The owners want to protect the value of their investment – the more revenues they control, the more protected they are against variation in the marketplace. That also seems to be part of their opposition to the NHLPA’s growth estimates – the owners aren’t convinced the US/Canadian dollar exchange rate can be relied upon going forward. Instead they argue much of the growth from the last seven years has come about from the strengthening of the Canadian dollar and nothing else.

Just as things will start to get tough for the owners once the games start to not be played, things will get tough for the players once they start to not be paid. They have escrow money coming in on October 15th. After that, other than maybe players on the Oilers, Flames and Habs, there won’t be any more money coming in. Of course these guys could go into a bank and get themselves a loan, but they still won’t be getting paid.

Defining the owners

The owners fall into three groups, all with conflicting interests in a lockout. At the top, there are the dozen or so highly profitable teams, teams that will be unhappy about not generating revenue but will also be quite happy to reduce their expenses – if it takes a lockout then so be it. There’s a calculation they will have to make though – at what point is the lockout actually making things worse off?

The second group of owners are the middling teams, who are just getting by. Some are breaking even, others are perpetually in the red. If they can cut down costs, then hockey becomes a not-totally-outrageous enterprise. Until then, it’s not. By locking out the players and keeping their rink closed, they are not spending money but nor are they generating any money either. Their breaking point is when their bills start getting hard to pay with just the money in the bank.

Many of these teams have collected a fair share of their season ticket monies, for instance, but at some point that cash will start to run thin. Think of the Nashville Predators – the Flyers blatantly structured their offer to Shea Weber as a challenge to the Preds’ cash flow. Nashville was able to cover Weber’s enough first signing bonus, but how much cash is left in the bank? Will a bank be willing to extend the Predators’ owners a loan to cover their near-term costs? Certainly, but for how long?

Group three are the bottom-end teams, like the Coyotes and the Islanders. Forbes estimates that the league’s weakest siblings generate just a third of what the Leafs – the league’s table leaders – generate in revenue. These teams are the most happy to not be paying out salaries, they have almost no money to begin with. A lockout is extremely good for business, they don’t spend any money. They can stay out for a long time because if they are open, they bleed money through expenditures.

Whither the Canucks’ ownership?

This leaves us contemplating the Canucks’ true position. It’s a consideration of the Aquilini brothers as businessmen, as well as community leaders. Their community investments will continue – things like the Canucks Autism Network and their coaching programs. Further, as a marketing property, they will still be selling off-ice products, but probably not at the same level. For example, in the last lockout, sales of the EA Sports NHL franchise dipped 50 per cent. But the NBA actually saw increased sales of their video games. This might also explain why EA launched NHL ’13 this week, before the lockout. Get the sales out there, detach the fan from their feelings about the NHL situation and just have them think about how much fun the game is to play.

And yet there’s the chance to reduce their costs. Any businessperson will tell you that a chance to reduce costs is almost always a no-brainer. Last time out, the Toronto Maple Leafs were able to cut their payroll by $26 million, simply because the cap came in at that much less than they’d been paying out in the pre-salary cap days. Any chance to get a roll-back will suit Vancouver’s owners nicely, even though they’ve spared no expense in assembling the team’s current roster.

The Canucks are still in a gate driven business. With that revenue not coming in during the lockout, teams like the Canucks will be doing a careful calculation – how long until their profits are being seriously dented by the lack of incoming cash?

The bottom line: any game not played is lost revenue and no owner will be happy about that. Lack of revenue, more that anything, may mean a shorter lockout. We’ll see.

Recent articles from Patrick Johnston