Canucks Army Preseason Prospect Rankings: #6 Nikolay Goldobin

6 years ago

Let me say in no uncertain terms: I love Nikolay Goldobin. I love that he’s fast. I love that he is an unapologetic one-way player, and I love that he makes weird folk-art statues of cows made out of scraps of wood.

He strikes me as exactly the type of player Don Cherry would hate, which truly makes him a man after my own heart. But therein lies the problem. The league is largely populated by what are essentially, whether they want to admit or not, slightly more elegant Don Cherries.

pGPS (and it’s predecessor, PCS), is in my opinion the most interesting and enlightening thing Canucks Army has ever produced. But it has limitations. The biggest is that by nature it cannot address the fact that players do not exist within a vacuum, and using games played as a measure of success is something that only exacerbates this issue. pGPS can tell you how many statistical cohorts of a given player went on to play 200 or more NHL games, how much those players produced on average, and what the expected value of the player you’re analyzing will be. What it can’t tell you, and this is it’s biggest flaw, is how many cohorts should have been successful, productive NHL players. The concept of “should” is very nebulous, and not something that many analysts, traditional or statistical, would have much use for, given it’s subjectivity. That doesn’t mean it’s not an important consideration, though.

The implicit assumption of a predictive model like pGPS is that NHL executives and coaches don’t make mistakes, that the NHL is a perfect model of meritocracy. But we know this isn’t any more true of the game of hockey than it is of society at large, and only the most simpering partisan would believe it to be as such. Each player has a unique set of circumstances, a unique set of obstacles to overcome, and a finite number of spots open to them.

I guess what I’m trying to say is, I think there’s a version of the NHL that exists, or could exist at some point in space-time, where there’s no question as to whether or not Nikolay Goldobin belongs on an NHL roster. In this respect, you could consider this profile a spiritual sequel to the one I wrote on Jordan Subban a few days ago. They’re both players with very specific high-end skills who struggle with the defensive side of the game and may never see the light of day because of it.

In some ways, Goldobin’s first game as a Canuck told us all we needed to know about him as a player. He scored a beautiful goal, maybe on of the best Vancouver had seen all season, but he cheated to do it, and he was swiftly punished for it by then-coach Willie Desjardins, who let Goldobin rot on the bench for all but 30-odd seconds of the remainder of the game. That’s Goldobin in a nutshell. Flashy and defiant in the face of authority. It’s a great way to get the fans on your side, but it’s probably a losing proposition if you’re looking to have a long, successful pro hockey career.

What Desjardins struggled with regarding Goldobin, and arguably the game of hockey in general, is the concept of risk management. There is no such thing as risk-free hockey. It has risk bred into it’s DNA. There is risk inherent to every decision a player makes, every selection made in the draft, every trade, every transaction.

What Desjardins failed to understand, and what most of us in the game of hockey still struggle with, is that cheating isn’t inherently bad. All a player has to do is be successful at it one more time than he fails to be a useful player. I don’t pretend to have a crystal ball, but Goldobin might be that player.

John Tortorella has said a lot of silly things over the course of his career, but he was absolutely right about one thing: safe is death.

Nikolay Goldobin? He’s the opposite of that.

Qualifications

We’ve changed the qualifications up just a little bit this year. Being under the age of 25 is still mandatory (as of the coming September 15th), but instead of Calder Trophy rules, we’re just requiring players to have played less than 25 games in the NHL (essentially ignoring the Calder Trophy’s rule about playing more than six games in multiple seasons).

Graduates from this time last year include Brendan Gaunce, Troy Stecher, and Nikita Tryamkin, while Anton Rodin is simply too old now, and Jake Virtanen is not being considered solely as a result of his games played.

Scouting Report

Failed to load video.

I’ve seen Goldobin described as a “pure goal-scorer” more than a few times in the past, but I think referring to him as such is a case of unnecessary pigeon-holing. Instead, I see him as a very gifted player with a complete offensive toolkit. His most immediately noticeable asset is his wrist shot, but he possesses the explosiveness and creativity to set up teammates as well. In short, he’s the type of player that gives depending players fits. Give him too much space, and he’ll make you pay, but get drawn in too much, and suddenly the puck is on his teammate’s stick and in the back of the net.

When it comes to players of Goldobin’s ilk, there are often concerns about defense. Those concerns are usually overblown, but in Goldobin’s case, he’s guilty as charged. In his limited time with the big club last season, he posted some of the league’s worst defensive numbers, controlling a paltry 42.7% of shot attempts and allowing 67.7 shot attempts against per hour while on the ice. Some of this can probably be attributed to playing with Brandon Sutter, but he still struggled to get his numbers up to a respectable number with better linemates.

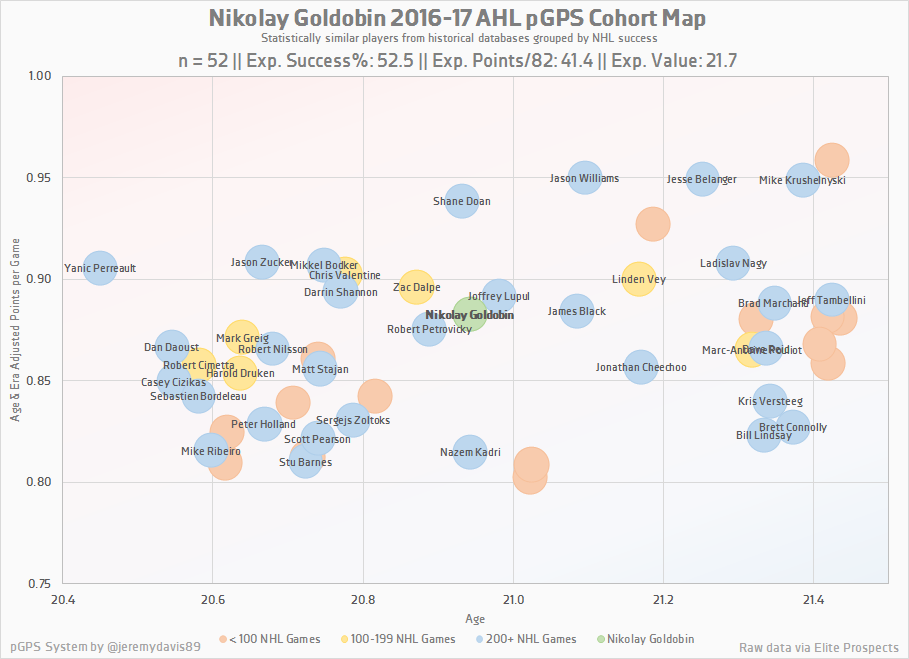

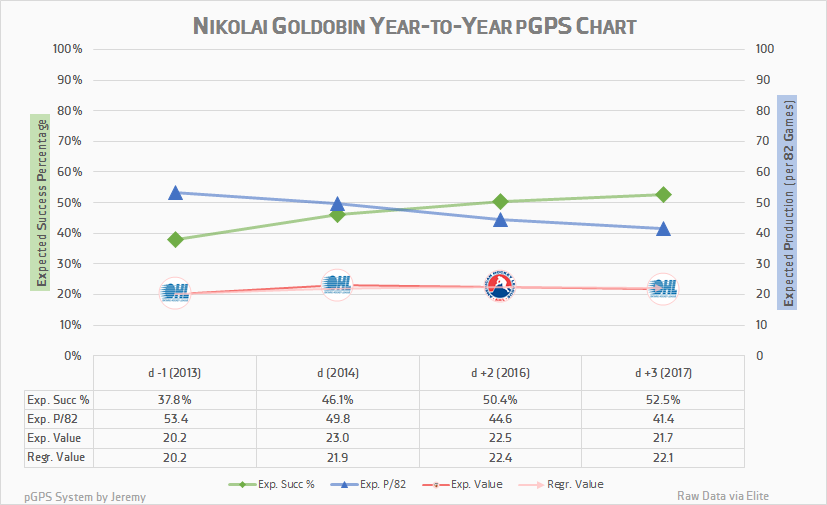

Goldobin is one of the Canucks’ most impressive prospects from an analytical perspective, carrying an expected success percentage of 52.5%, with an expected points/82 of 41.4. As you might expect, there are a quite a few offensive forwards among Goldobin’s statistical cohorts, including Mikkel Boedker, Joffrey Lupul, Jason Zucker, and Brad Marchand.

Interestingly, Goldobin’s expected success percentage has steadily improved from year-to-year, while simultaneously his expected production has fallen by 3-5 points in each of the past three years. This strange inverse relationship between the two statistics is almost certainly meaningless, but it’s interesting nonetheless.

My biggest concern regarding Goldobin is that he’s going to need to get sustained NHL action at some point very soon, but given the team’s most recent signings, it doesn’t appear that there will be any room for him this season. That doesn’t bode well for a player who’s probably already fighting an uphill battle given the nature of his game.

Though they’re incredibly rare, there are players that manage to consistently be sub-50% in shot attempts and above 50% in goals-for. Whether Goldobin can be that player is another story. He certainly looks like the type of player that could fit that mold, but he’ll need to improve his two-way game even to get to that level. If the Canucks hit a home run on Goldobin- and that’s a big if- he’s got all-star written all over him. What’s far more likely is that he settles comfortably into a Sam Gagner-type role, needing to be sheltered at even-strength, but capable of wreaking havoc on the man advantage. The biggest question is whether or not the Canucks have the patience and understanding to let him do that. Their track record with young players is hit-or-miss, and Goldobin is bound to be among the most frustrating players they’ve ever dealt with.