The Flying Take: Elias Pettersson Stats, Shotgun Jake Shots, and a Bit of Poetry

5 years ago

Author’s Note: I’m going to be trying something new this season. Lots of interesting stories or observations materialize over the course of the season that don’t necessarily merit a 2000-word deep dive, but still warrant attention. As such, I’ll be compiling stories, thoughts, and observations in this column, hopefully on a weekly basis. Introducing The Flying Take:

1. We’re going to talk about poetry again.

For those of you that need a recap, the last time we devoted article space to the works of Robert Frost was in March of last year, when our beloved Petbugs responded to a feud between the blog and a member of the Vancouver media that I won’t go to the trouble of rehashing here.

I want to turn your attention to another Frost poem, The Road Not Taken:

“Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,And sorry I could not travel bothAnd be one traveler, long I stoodAnd looked down one as far as I couldTo where it bent in the undergrowth;Then took the other, as just as fair,And having perhaps the better claim,Because it was grassy and wanted wear;Though as for that the passing thereHad worn them really about the same,And both that morning equally layIn leaves no step had trodden black.Oh, I kept the first for another day!Yet knowing how way leads on to way,I doubted if I should ever come back.I shall be telling this with a sighSomewhere ages and ages hence:Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—I took the one less traveled by,And that has made all the difference.”

I promise I’m going somewhere with this.

I must admit I’m not much for poetry, unlike some of the authors that have plied their trade here (take J.D. Burke, for instance, who can quote Percy Bysshe Shelley like the unrepentant nerd that he is). That probably goes a long way towards explaining why I’m focusing on arguably the most famous American poem of all time. What interests me more than the poem itself is what readers have taken from it, and how it may be the most wildly misunderstood work in American literary history.

Contrary to popular belief, The Road Not Taken is not a celebration of rugged individualism. It is not a plea to the reader to take the road less traveled. A close reading reveals that the passing of travelers through the two roads “had worn them really about the same”, and there is no meaningful difference between them. The speaker is looking back and assigning meaning to what was essentially an arbitrary decision. The poem is about how we construct stories around even the most mundane events in our lives.

It’s been on my mind a lot as I’ve watched the amazing start to Elias Pettersson’s career, and pondered the question of “sustainability”. Through 11 games, Pettersson has scored on 34.5% of the shots he’s taken. Surely that’s not sustainable, right?

Well, yes and no. The problem with citing shooting percentage as an indication of whether a player’s offence is sustainable or even earned is that conversion rate alone doesn’t tell us much. You don’t get a cookie for pointing out that a player who scored one of his two shots last night isn’t going to magically score on every second shot he takes.

What you’re really doing is trying to preemptively determine the story we’ll be telling in year’s time. The assumption when we see a high shooting percentage is think of a player like Matt Beleskey, who converted at a 15.2% clip in a contract year with the Anaheim Ducks, cashed in, and hasn’t eclipsed 15 goals since.

The problem with this line of thinking is that good players go on shooting percentage benders all the time. Let’s use the recently retired Henrik Sedin as an example. He had a 20.5% shooting percentage in his sophomore season. Was that unsustainable? Technically, yes, but he still finished his career with over 1000 points, multiple 70+ point seasons; during a handful of which he shot above 15% (including his Art Ross Trophy-winning season).

Pettersson is obviously going to regress offensively, but maybe not as much as you’d expect from a player who’s scoring on over a third of his shots. He’s been among the league’s best players at producing shot attempts off the rush, which has been shown to result in more goals than shots generated through zone time; and his most common linemate at even-strength, Nikolay Goldobin, is converting on a measly 4% of his 5-on-5 shots. So it’s not unfair to think that when Pettersson inevitably comes back down to earth, it’ll be a gentle touchdown rather than a crash landing.

Much like the Frost poem, when we look back on Pettersson’s season, we’ll be constructing a story about it. The question is, will we be talking about his first eleven games as an unsustainable run that inevitably came crashing down, or as an unbelievably hot stretch in an impressive rookie season?

My guess is the latter.

2. Another player who’s been getting a lot of love due to a hot start is Jake Virtanen, but I’m feeling much more torn on whether or not he can keep it up. Like Pettersson, his shooting percentage is on the high side, at 18.2%, but unlike Pettersson, he hasn’t generated many shots off the rush. He’s currently attempting 0.31 rush shots per 60 minutes, down significantly from his team-leading 0.85 last season. In fact, his shot rates in general are down significantly from his career average. It doesn’t make for the best combo with a high conversion rate. What gives me pause, however, is that for most of his career up until now, he hasn’t exactly shot to kill, so to speak. It’s been my biggest frustration with him since he entered the league. On countless occasions, he’d cross the blue line with time and space, only to fire a clapper straight into the goalie’s chest from thirty feet out. It worked well for him during his time with the Calgary Hitmen, but it’s not going to beat many NHL goalies. That’s a big part of why his goal-scoring hasn’t translated to the NHL as well as some of his peers from the 2014 draft class. It’s tough to say, but Virtanen’s lower shot rate could be an indication he’s trying to pick his spots better rather than just shoot from anywhere. He’s got one of the best cannons on the team, so I think they can live with a shot or so less per hour if it means he’s trying to hone his offensive skills. Only time will tell if it’s just a nice run or a sign that there’s more consistent offence on the horizon.

3. Canucks fans understandably can’t get enough Elias Pettersson stats, so here’s another for you: In just 11 games, Pettersson has become the third-most productive player from the 2017 draft class, behind only top two picks Nico Hischier and Nolan Patrick. I’d imagine the Glass/Mittelstadt/Vilardi truthers may already be regretting speaking too soon.

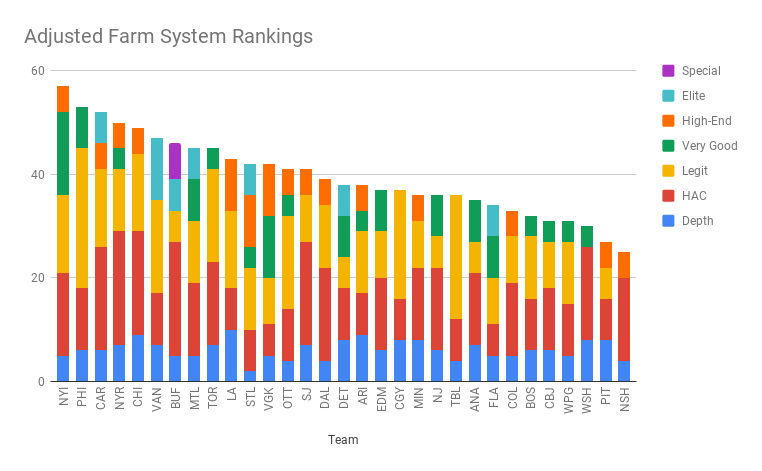

4. The Canucks play the Buffalo Sabres this morning, which means that the graduates of what The Athletic deemed to be the two best farm systems in hockey face off against one another on the national stage. You may recall that this summer, Corey Pronman made waves in Vancouver by declaring their prospect pool the league’s second-best, behind only the aforementioned Sabres. As the two teams get set to face each other, I thought it might be fun to take a look at an exercise I undertook this summer for an abandoned article.

In Pronman’s rankings, he laid out a basic methodology that included seven tiers of player quality:

- Special prospect: Projects to be one of the very best at their position in the league

- Elite prospect: Projects to be top 10 percent of the league at their position.

- High-end prospect: Projects as a legit top-line forward who can play on your PP1/top pairing defenseman.

- Very good prospect: Projects as a top-six forward/top-four defenseman/starting goaltender.

- Legit NHL prospect: Projects to play, probably not in a top role, but is close enough that he could realistically get there.

- Have a chance: Probably not an impact guy but could play in the league and has the toolkit to have an outside chance to be a real player. Have a chance refers to probability to be a good player, not his probability to play NHL games.

- Depth: Player who doesn’t have the skillset to play high in your lineup but could fill out your roster and/or be an injury call-up option.

Overall, I found the rankings to be very well done in terms of providing a snapshot of each team’s prospect pool. The issue with ranking an entire pool is always volatility, though; especially when a single elite prospect can tip the scales dramatically in one direction or another. So, for fun, I assigned a numerical value from 1-7 to each of Pronman’s tiers. Then I added them up, and came up with an approximation of how he ranked each team’s prospect depth:

The results differed dramatically. Teams were rewarded more for having a large quantity of decent prospects than for having one or two elite ones. The Islanders leaped into first place thanks to their stellar 2018 class, while the Canucks and Sabres fell back 4 and 5 spots, respectively. Ranking for depth also meant teams were punished less for their top prospects graduating. For instance, Philadelphia fell just one spot from their place atop last year’s rankings, as opposed to the 11 they dropped in the actual rankings. ( I would provide more details regarding Pronman’s complete list, but the Athletic is a wonderful resource that relies on subscriptions for revenue, and I don’t want to go beyond fair use.)

Obviously, it’s an incredibly unscientific exercise that has it’s own issues, not the least of which is that seven Guillaume Briseboises do not equal a Rasmus Dahlin. Still, I think it serves as an interesting companion to Pronman’s in-depth look at all 31 prospect pools.

5. Speaking of the Sabres, Casey Mittelstadt has been an interesting case study in the reactionary tendencies of armchair scouts. Once touted as a dark horse candidate for best player in the 2017 class, Mittelstadt has already generated whispers of “bust” from some of the more impatient corners of the internet due to his somewhat inauspicious start. All in all, he’s scored at a half-a-point-per-game pace over his 22 career NHL games. That’s far from deeply concerning.