The Canucks as Labour Warriors

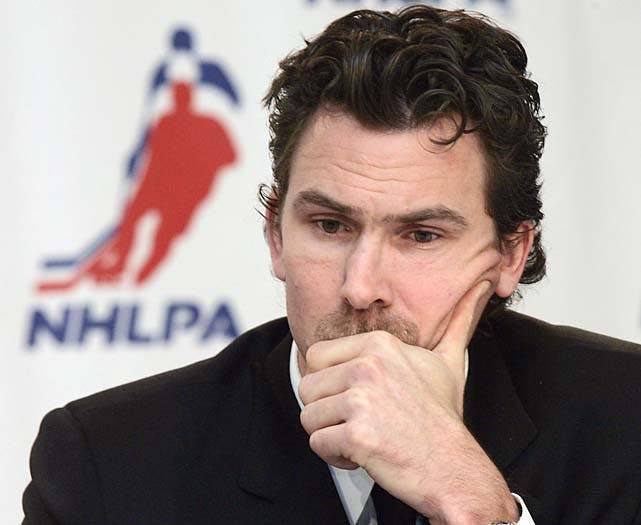

Those were hard days for Trevor Linden and the NHLPA

Labour law has a long tradition in Canada, and it’s no surprise that a game so interwoven with Canada’s national identity is currently watching as its players seek to take advantage of the rights that have been afforded to them. Efforts in Quebec and Alberta may only delay the inevitable, but there’s an intriguing local angle to sports labour law that is worth considering.

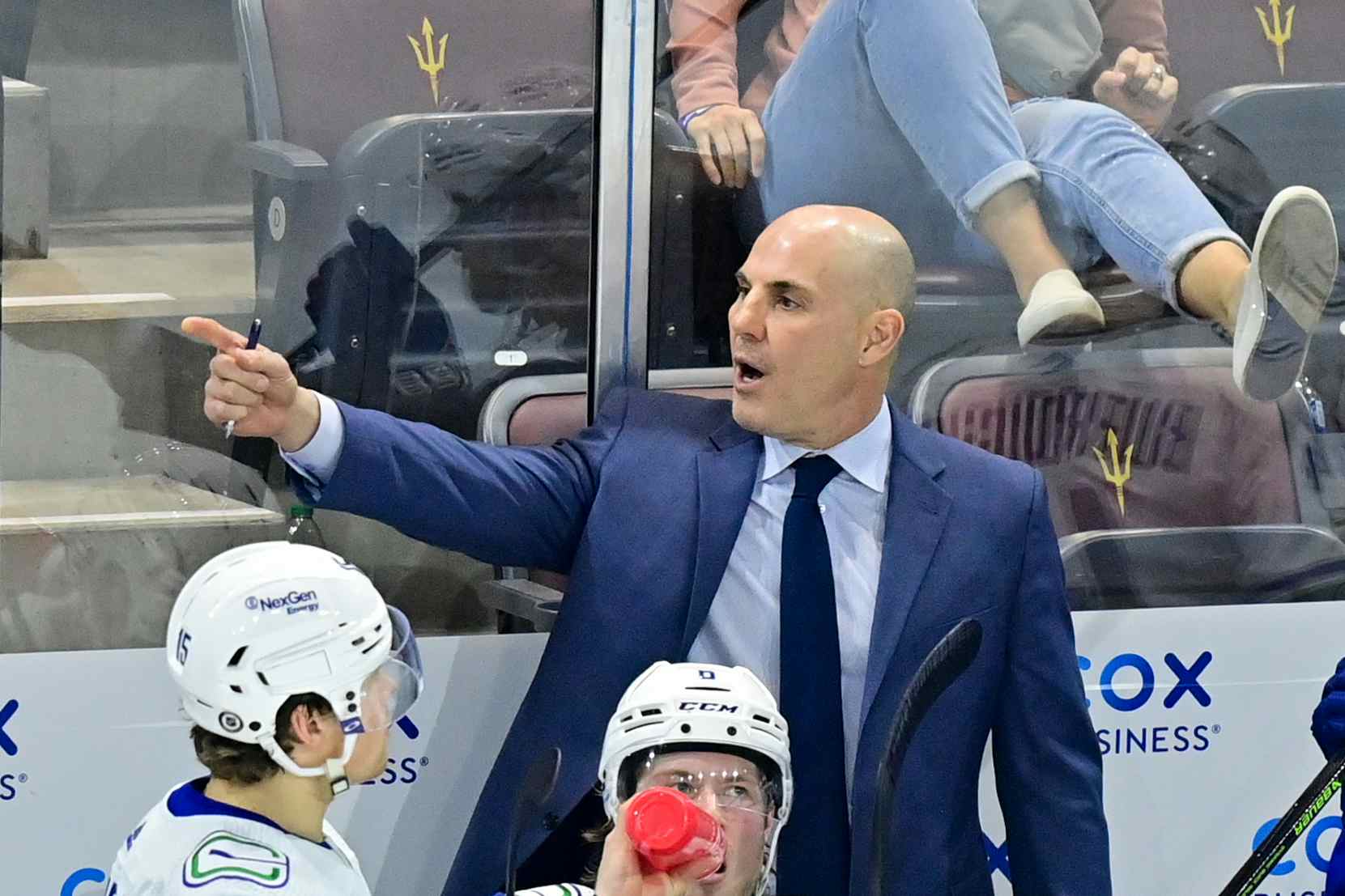

The Canucks players in 2005 tried to certify themselves as a unique union in the province of British Columbia. Ultimately they lost the case, and weren’t permitted to certify, but the story is particularly relevant today given the announcement that Canadiens players will move to block a lockout in Quebec under the unique circumstances afforded them. More on that later.

In 2005, players in both Montreal and Vancouver sought to have themselves certified as separate, unique labour unions. We should get into some quick background at this point, and explain that the NHLPA is not certified in Canada, which makes their bargaining relationship somewhat problematic. Arrangements that are made on the players behalf – the CBA – aren’t codified in BC, but the rules are respected nonetheless. It’s like the written and unwritten rules of parliament: it has long been understood that owners and players in Canada would respect the rules as laid out in the USA. Thus, all teams in the NHL operate under the CBA, even though Canadian teams fall technically "outside" its jurisdiction.

The argument presented by the would-be BC-NHLPA was that Canucks players weren’t correctly represented under BC labour law by the existing NHLPA, and that they should be allowed to certify as a separate union to represent their rights to the NHL and the Canucks.

The Quebec process was dropped when the lockout was settled, but the BC case carried on, being ruled on twice by the BC Labour Relations Board, which eventually denied the application.

Ultimately the BC board rejected the claim because the NHL and the NHLPA already existed and had a long-standing labour arrangement; adding a new bargaining unit would in fact destabilize what was a long-standing, functional relationship. The fact that owners had locked out the players was not reflective of long-standing dysfunction.

The law won’t allow these sorts of tactical moves to be used as a bargaining tactic; a union can’t pretend it’s not functioning properly if it’s in fact functioning properly. Similarly, the NHLPA threatening to de-certify, an idea which has been publicly mooted on more than one occasion, would only be acceptable if the players could prove that the union itself was acting in a grossly negligent manner.

It was a move by the NHLPA to rectify a situation that is a rather curious one, but not really all that unusual. Players in Canada aren’t actually members of a Canadian union, though they are acting as a collective group to further their goals. Even if the players aren’t in a Canadian-recognized union, they still have many rights as workers, which is exactly what the current move to stop the lockout in Quebec is all about. Under Quebec law, owners are not allowed to lock out employees if the employees aren’t in a recognized union.

Also of interest is the baseball umpires case that was brought to the Ontario Labour Relations Board in 1995. Major League Baseball had locked out its umpires, but a ruling by the OLRB found that MLB had not followed Ontario labour law and were thus not allowed to lockout their umpires in Ontario. This set a precedent for subsequent sports-labour actions; each jurisdiction’s rules would have to be respected. Thus the move in the last lockout to use the labour relations process in BC and Quebec. With the BC (and separate certification) door now closed, it makes sense that the NHLPA and its members would look to use other provinces’ labour policies to their benefit.

The players for the Oilers and the Flames have also intiated procedures in Alberta – ironically enough by using provisions that might be seen as actually existing to help owners. It all adds up to a clear push by the NHLPA to be seen as negotiating in good faith, while placing doubt on the sincerity of the owners. How that really gives them an advantage is unclear – the labour dispute certainly has a PR angle, but the settlement doesn’t really take public opinion into consideration.

Recent articles from Patrick Johnston