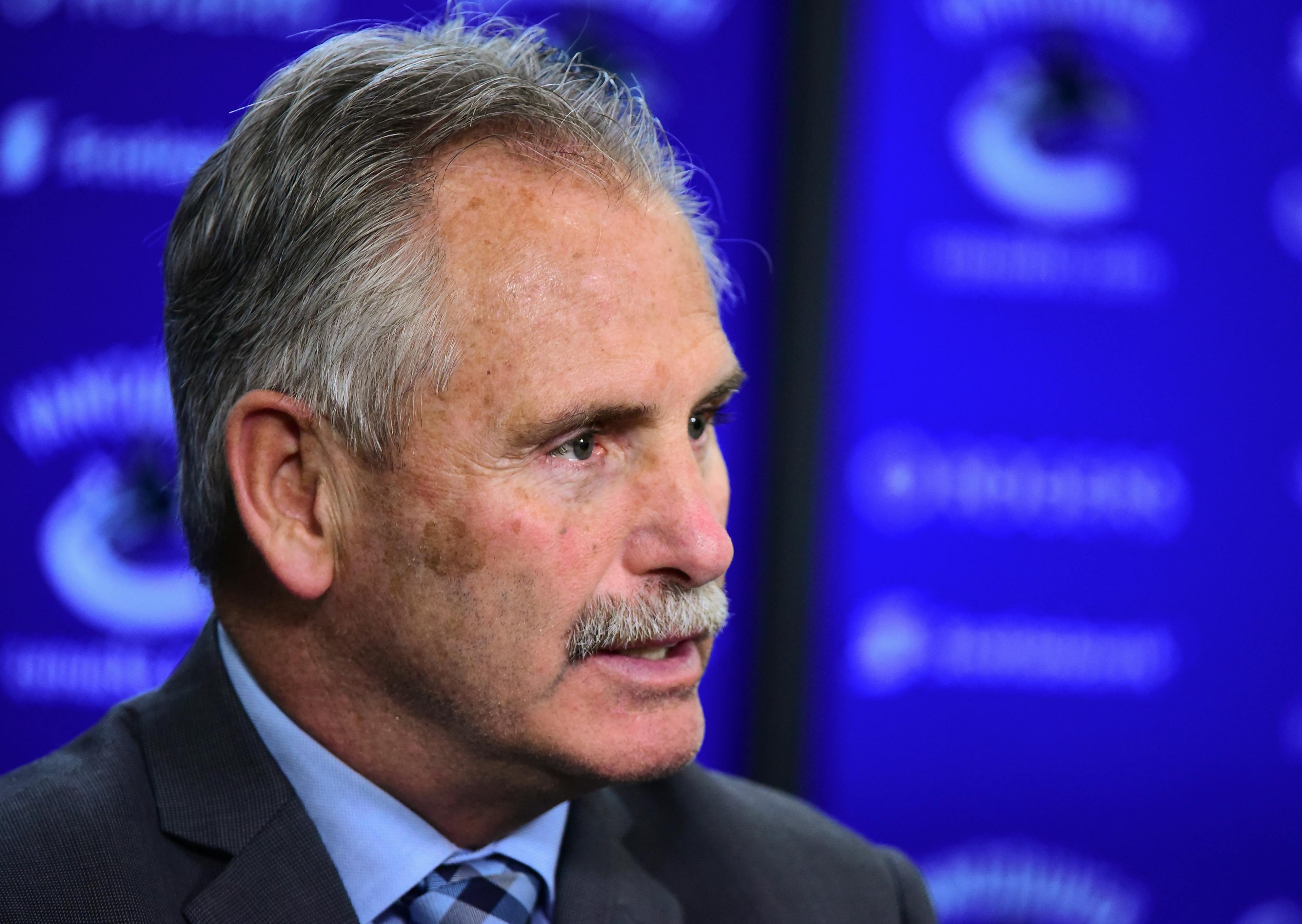

Former Canucks head coach Willie Desjardins said all the right things when he got the job. At his introductory press conference, Desjardins preached pace, tempo and a puck possession oriented offence that would focus heavily on gaining the zone with control.

It was music to the ears of Canucks fans who’d spent a year suffering the ill-fated John Tortorella experiment and the boring brand of hockey it engendered.

That wasn’t the first time Canucks fans had been lured in, though. Once bitten, twice shy, or so the saying goes. Desjardins had to prove he meant business, and prove his mettle he did.

The Sedin twins — worked into near-combustion by the bench troupe that preceded Desjardins — played about two full minutes fewer each game than they did in a season prior and to great effect. Each saw an increase in point production in the twenties for it.

Desjardins was instrumental in that renaissance. Part of why the Canucks were able to get more out of each Sedin while playing them less was the club’s commitment to playing with control of the puck and foregoing the everything and the kitchen sink dump and chase forecheck that shut them down better than any checking line ever could. And of course, the ageing Sedins benefited from the increased rest, too.

The Canucks couldn’t do that without valuable, if underrated (certainly in retrospect) utility pieces like Brad Richardson, Shawn Matthias and Nick Bonino picking up the slack left by the Sedins’ decrease in ice-time.

Matthias benefited from the run-and-gun transition attack the Canucks employed better than perhaps anyone, leading Canucks with 500 0r more minutes at even strength in goals-per-hour with 1.08. Richardson contributed the ninth-most points per hour at even strength, which proved commensurate with his salary range and role. Bonino led the team in points-per-hour with over two.

Vancouver employed useful depth pieces throughout their lineup and Desjardins mantra of allotting each a slice of the ice-time pie, while fodder for jokes years later, was exactly what led the Canucks to the 101 point campaign they enjoyed in his first season.

While many are right to point to the Canucks’ success in one-goal games as a harbinger of the regression that followed a season later, I think that undersells the efficacy of the Canucks that season.

It’s hard to believe now, but Vancouver was outscoring their goaltending problems until Eddie Lack took the reigns from Ryan Miller to end the season. Teams that generate offence off the rush generally shoot at a higher clip. There was a method to the madness, and for every break the Canucks got I’m just as confident they make the playoffs that season if a few went in the opposite direction.

Yes, the Canucks lost in the first round that season and Desjardins looked completely lost therein, but he was a first-year coach in his first NHL playoffs. In theory, I’m certain there are lessons from that six-game series with the Calgary Flames that he’d like to put to practice if the opportunity ever arose.

Everything changed, though. Management either dealt the players that made their team a three-line threat on any given night away for pennies on the dollar or watched them walk on bargain deals in free agency.

In brief glimpses, Zack Kassian was one of the Canucks’ most productive goal-scorers at even strength, and for that Canucks general manager Jim Benning placed Brandon Prust in his stead. The Canucks could have allocated funds towards retaining Richardson and Matthias, but instead lit six-plus million dollars on fire with inexplicably terrible contract extensions for Luca Sbisa and Derek Dorsett — deals that manage to look worse and worse with each passing year. Bonino and accompanying assets became Brandon Sutter, a player whose last season is the 768th most productive for forwards with 1500 or more minutes among a total of 773 forwards.

I wouldn’t classify any one of these decisions as a death knell for the franchise by themselves. It was a death by a thousand cuts kind of incremental loss after loss approach to roster construction, though, which undercut everything that made Desjardins’ system work.

It’s a funny thing that Desjardins legacy will be that of a veterans’ coach who stifled creativity and offence in the name of structure. Almost ironic.

In even his second season, in spite of bleeding offence the summer prior, Desjardins continued to try and run an offence-first, up-tempo system. Consequently, the Canucks bled goals and couldn’t score enough to cover those deficiencies.

Top to bottom, the Canucks, an ever reactionary franchise, wasted no expense in addressing the latter of those ills and hoped for the best where the offence was concerned. It’s no surprise, then, that Desjardins shifted his emphasis to that of a defence-first coach even if his decisions don’t necessarily reflect as much when tested with unshakeable facts and evidence. Certainly, it’s what he hoped to accomplish when he played the Jayson Megnas and Michael Chaputs of the world as frequently as he did.

But therein lies the problem. Fault the Canucks for leaving Desjardins with sparse options, but he always seemed to relish picking the worst of the lot. Every coach has their blind spots, but there were times this season where one could sincerely ask if Desjardins had any viewpoints. One could reasonably argue, too, that no coach deployed what they had to work with worse than Desjardins did.

I remember at one point in this season, an executive from another team remarked that there wasn’t an easier coach to game plan for in the entire league. The constant and unbreakable rotation from senseless line to senseless line made playing the Canucks shooting fish in a barrel.

All the systemic adjustments Desjardins made, whether in game or out, weren’t enough to compensate for the lack of talent and the poor use of the talent available to him.

And I think that’s something that might get lost in all this. Desjardins remains, right to the bitter end, someone that an NHL team should feel confident entrusting a white board to in some capacity. The X’s and O’s were never a shortcoming of Desjardins’, even at the worst moments.

Fans will lament that Desjardins didn’t deliver the rebuild they wanted with the Canucks’ on-ice product, and perhaps that’s fair, but his goal was never to rebuild. The Canucks front office was bullish that they’d improved this team over the summer and confident of a return to the playoffs. Rightly or wrongly, Desjardins isn’t alone in not entrusting the youth with accomplishing that end, and I don’t think we can blame him for being singular minded with that goal while the people above him shift goalposts weekly, depending on who’s in front of the microphone.

The tragedy is that a coach at Desjardins’ age might not get a second chance to reshape the image management forced him to wear. His body of work with the Canucks doesn’t exactly instil confidence, and again, that’s probably fair. Talk about working with a garbage hand, though.