The Canucks celebrated Black History Month for the first time last season with a pre-game ceremony honouring some of the team’s black players and by sporting special BHM-themed warmup jerseys. It was the beginning of a tradition that carried over to this season and will hopefully continue for the foreseeable future.

Celebrating Black History is something that has been long overdue for both the NHL and the Vancouver Canucks, who have had a number of notable black players pass through the organization in its 53 years as an NHL franchise.

In last year’s BHM game, the team honoured Claude Vilgrain, the first black player in team history, with a ceremonial puck drop. The team has also released a pair of videos featuring Dakota Joshua and Nathan Lafayette sharing their stories of life as black hockey players.

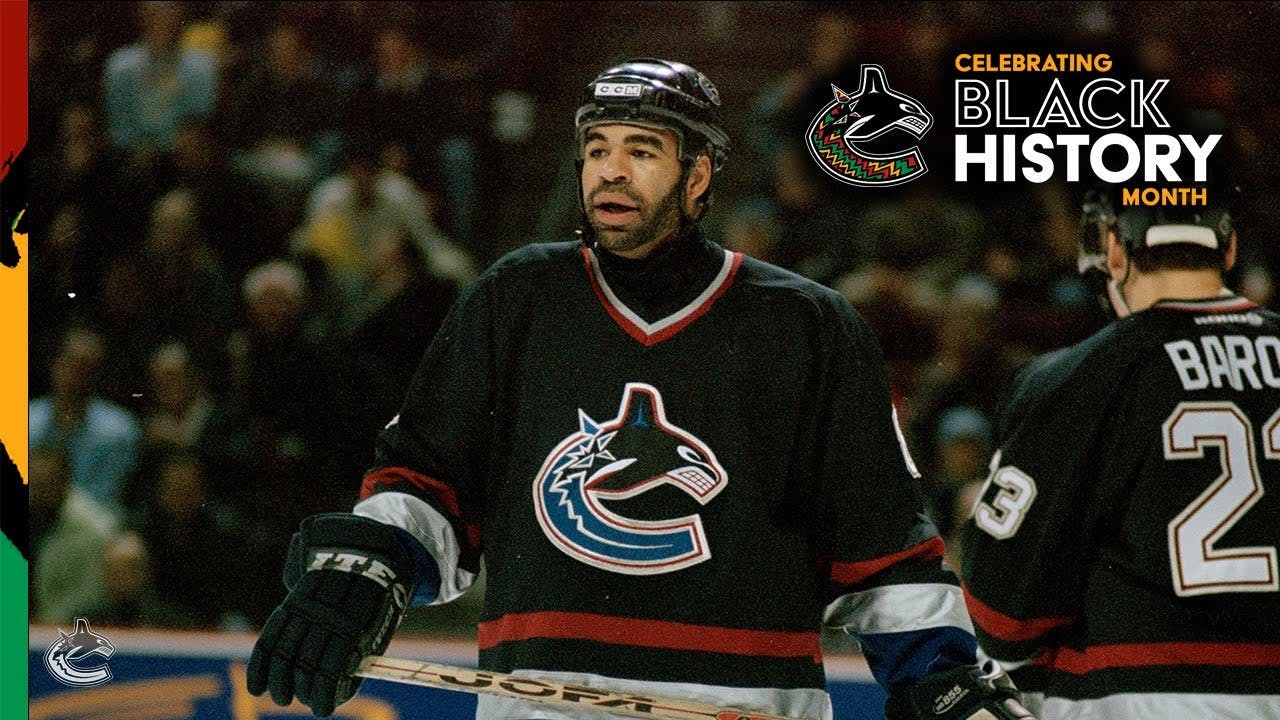

Another player who deserves to be honoured in a similar fashion is Donald Brashear, the longest-tenured black player in team history, and arguably its most accomplished.

Some observers might balk at the idea of celebrating Brashear, who was known more for his fists than his hockey IQ, and played during some of the leanest years in the team’s memory. But those people fail to understand the magnitude of Brashear’s accomplishments, both on and off the ice.

At best, Brashear’s role in hockey’s collective memory has been as a victim — of bad luck, racism, and one of the most notorious stick-swinging incidents in league history in which he suffered both a grand mal seizure and a grade-three concussion — and at worst as a goon with marginal hockey abilities.

When most hockey fans think of Donald Brashear, they think of the McSorley incident, or him working the drive-thru at Tim Hortons after running into financial and substance abuse issues. Folks in Vancouver might know that he holds the franchise record for penalty minutes in a single season, but not that he eclipsed 25 points three times at the height of the dead puck era. They also might not realize that his pro career lasted nearly a quarter-century, from 1992 to 2015. Or even that he became the first black NHL player to reach the 1000-game threshold. (Especially because he has been frequently and misleadingly credited as merely the first American-born black player to play 1000 games, including in the Canucks’ own video tribute, despite reaching the milestone several months before Jarome Iginla did in February 2010.)

ICYMI: @MapleLeafs forward Wayne Simmonds became the fifth Black player in NHL history to reach the 1,000-game milestone. #NHLStats: https://t.co/oo9hPR2DnE pic.twitter.com/GpoBFde40w

— NHL Public Relations (@PR_NHL) March 6, 2022

But as impressive as his on-ice accomplishments were, it’s his life off the ice that really underscores the uniqueness of Brashear as an NHL player, and why his story serves not just as an inspiration for other black players, but also for anyone who has struggled against poverty, racism, abuse, and addiction.

Brashear was born on January 7, 1972 in Bedford, Indiana to French Canadian Nichole Gauthier, and African American Johnny Brashear. The two met in 1967 when Johnny, then 22, was on weekend leave from the U.S. Air Force radar station in St. Albans, Vermont, just south of the Canadian border.

Nichole was just 19 when she became pregnant with Donald, and her relationship with Johnny quickly turned violent. In the midst of a years-long struggle with alcoholism, Johnny inflicted severe physical abuse on his son from a heartbreakingly early age. He would whip Donald with belts, electrical cords, or whatever else he could find and even threw him across a room in a particularly heinous incident when he was just six months old.

After suffering beatings from her husband three nights in a row, Nichole concluded she was likely to either die or suffer a nervous breakdown if she didn’t leave her husband. She snuck away under the cover of night and hitchhiked her way back to Canada, but was unable to take her children, including 18-month-old Donald with her.

She would return to collect her two elder children shortly thereafter, but did not seek custody of Donald for another four years. This was at least partially attributable to her new husband, Gerard Roy, who harboured racist attitudes towards black people. Roy had tried unsuccessfully to convince Nichole to give her children up to social services and did not want another biracial child in the house.

At age five, he moved to Lorretteville, Quebec to reunite with his mother, two elder siblings, and his new half-brother. But sadly, things did not improve. Donald once again suffered traumatic physical, verbal, and psychological abuse at the hands of his new stepfather. Roy would often berate his stepson for struggling to learn to tie his shoes, and would frequently single him out for wetting the bed. While his other siblings slept together in a shared room with a bunk bed, Roy forced Donald to sleep alone in a cramped room across the hall, with a garbage bag tied around his waist. His half brother would later recall the profound effect the abuse had on both him and his older brother in a 2009 profile on Brashear in the Washington Post: “I hear him crying still in my head. I kept thinking how hot and scared he must have been in there. He must have been 7, I guess. It still haunts me.”

Fearing once again for Donald’s safety, Nichole eventually handed Donald over to the same foster system that she had grown up in. Donald would never be abused again, but his relationship with his mother never recovered. He broke off regular contact with his birth family, save for half-brother Danny, and spoke to Nichole only once during his time in the foster system.

Nichole would later remark that the psychological toll of Donald’s abuse left her with few alternatives to foster care: “I did it because he had the mental problems from all the trauma he had… he wouldn’t speak with me; he just kept saying you’re not my mother. There’s nothing I could do with him. There’s no way I could help him and I could see he was going to endanger himself. His father had really done a number on him.”

Johnny eventually got sober and sought forgiveness and atonement for the way he treated his son, but his only contact with Donald came in a message relayed to him through the aforementioned WaPo profile: “I saw on ‘SportsCenter’ once he taught himself to play piano. Everything he’s accomplished, he’s done it without me. Tell Donald I am proud of him; my mother never told me that.”

Donald’s assessment of his parents was more blunt. “[My dad] started the chain reaction of everyone splitting up and going our separate ways. I don’t call it forgiving. I think you decide to put it behind you and move on. But to say I forgive him? No, I will never forgive him.”

“I never had anyone to hold me and tell me they loved me,” he would later tell Gary Mason of The Globe And Mail. “I just didn’t have that in my life.”

After bouncing around between a few different homes for a year, Donald settled in with a foster family in Val-Belair, Quebec. He began playing hockey with his siblings at 8. He got along well with his new family, but money was tight, so he sold baked bread and garbage bags door to door to help pay for gear and league fees. Surprisingly, Donald’s first on-ice fight didn’t come until age 17, but off the ice, he would regularly get in fights at school with kids who taunted him with racial slurs dating back to elementary school.

Donald eventually played his way into major junior at 17 and produced at a decent clip over three seasons in the QMJHL. He quickly gained a reputation as a tough customer after one-punching an opposing player in his very first fight. He was also tremendously driven and in incredible shape, with his half-brother Danny recalling a time when Donald ran alongside him as he pedalled on his ten-speed bike.

Undrafted, Brashear signed as a free agent with the Montreal Canadiens in 1992. He played 3 seasons for Montreal’s AHL affiliate, the Fredericton Canadiens. After a quiet rookie season, he exploded for 66 points in 62 games and tied for the team lead in goals with 38 the following season. He eventually earned a call-up in 93-94 and registered his first NHL fight against the legendary Bob Probert. In 1995-96, he finally earned a full-time job in the NHL, where he would remain for the next 14 years.

His time in Montreal came to a close in 1997 when he was traded to Vancouver following a bizarre and intense screaming match with Habs coach Mario Tremblay. He finished the season with 245 PIMs split between both teams, the 7th-highest total that season, and even earned a spot on for the US international team at the IIHF World Championship during the off-season, where he scored 5 points in 8 games. He also played on a surprisingly effective line with Gino Odjick, which must have been one of the scariest pairings in NHL history.

Brashear’s first full season in Vancouver will go down as the high-water mark of his career. He finished the 1997-98 campaign with a new career-high of 9 goals, 9 assists, 18 points, and a league-leading 372 penalty minutes, a Canucks franchise record that may stand forever as its most unbreakable and is all the more impressive given that Brashear missed 4 games as the result of a suspension he incurred for retaliating against an Ian Laperriere sucker punch on Odjick.

Brashear would remain a feared enforcer as well as a reliable fourth-line player for the rest of his Canucks tenure. He scored a career-high 11 goals in 1999-2000, but is most remembered for his role in the aforementioned McSorely incident.

The vicious assault, suspension, and court case that followed have been discussed ad nauseum in the years that have followed, and pouring over the details again could fill several more articles, but suffice it to say the incident left a profound impact on both the league and Brashear, who suffered serious injuries on the play.

Astonishingly, the McSorely assault was one of three violent stick attacks on a black player in the span of just over a month, and while the victims all stated they did not believe race was a factor, it was a startling coincidence at best in an overwhelmingly white league.

To add insult to injury, Brashear was only ten months removed from being taunted with a racial slur by Bryan Marchment in a late-season game against the San Jose Sharks. Marchment would later claim that he was unaware his statement held racist connotations and insist, puzzlingly, that he “[did] not consider [himself] a racial person.”

Brashear was traded to the Flyers midway through the 2001-2002 season, amassing a career-high 32 points split between both franchises, and was also awarded the Pelle Lindbergh trophy for most improved Flyers player. He also played a pivotal role in the most penalized game in NHL history against the Ottawa Senators in 2004. It was preceded by another stick-swinging incident in an earlier game by Martin Havlat against Mark Recchi. With 1:45 left in the game, Brashear hit Senators enforcer Rob Ray from behind, which kicked off a series of fights between the two teams, each more ridiculous and over-the-top than the last. When asked after the game why he started the fight, Brashear replied with his own question: “Why wouldn’t I? Did you see the last game?”

He would later join the Washington Capitals in 2006, where he spent four seasons as something of a bodyguard to a reluctant Alex Ovechkin. Ovi was keen to fight his own battles as often as possible, but his time with Brashear clearly left an impact, given that he named him as the player he would most like to have on a hypothetical line with Sidney Crosby.

After signing a two-year, $2.8 million contract with the Rangers in 2009, Brashear’s NHL career eventually ended on August 2nd, 2010 when he was traded to the Atlanta Thrashers and immediately placed on unconditional waivers and bought out for the remaining year of his contract. While time in the NHL had ended unceremoniously, he was named enforcer of the decade by the Hockey News later that year.

Brashear then returned to the North American Hockey League (LNAH) in Quebec, known for its low salaries and high number of fights, where he had played during the 2005-06 lockout. He also briefly played for MODO Hockey of the SHL before retiring from pro hockey in 2015 at the age of 43.

Brashear racked up over 200 fights in the NHL over the course of his career, and several more in other leagues, averaging a fight roughly once every 5 games. He also spent some time as an amateur boxer, training with Joe Frazier; and embarked on a brief career as a mixed martial artist, defeating his first opponent by TKO in a stunning 21 seconds.

This was all in spite of his general ambivalence towards fighting, once telling a reporter, “I never liked fighting. I always wanted to be the type of player that plays hard, hits, body checks and scores some goals. But that’s not what they wanted me to be.”

Off the ice, Donald had mostly stayed out of trouble during his NHL career. He didn’t start drinking until he was 27 years old, but developed a dependency after a run of financial troubles following his retirement. While he’d grown accustomed to a relatively lavish lifestyle as an NHLer — he bought a lakeside property outright and was known to drive an Escalade and a pair of Lamborghinis during his time with the Flyers and Capitals — he looked poised to be able to maintain it with a pair of smart investments.

He bought a pair of condominium buildings and started a hockey stick company in 2015 called Brash87, with the goal of making high-quality affordable hockey sticks for kids. He even appeared in a season 10 episode of Dragon’s Den and successfully sought a $500,000 investment for a 20% stake in the company, but both ventures failed. Brash87 eventually filed for bankruptcy and Donald, who had retired debt-free, found himself millions of dollars in the red.

That debt worsened as he began to drink up to 30 beers a night; developed a pack-a-day smoking habit; and started abusing drugs like GHB, ketamine, and especially cocaine.

He had played pickup hockey with a group of friends from his NHL career including Simon Gagne, but they began to notice Brashear was looking more haggard and his appearances at games were becoming increasingly sporadic. The group eventually convinced him to check in to a rehabilitation centre in Arizona, but he left a week before completing the program, citing frustration at the counsellors’ insistence that he revisit childhood trauma. He returned to Quebec and quickly relapsed.

By this point, Donald’s financial situation had significantly deteriorated, and his continued drug and alcohol dependence only served to exacerbate the issue. He was eventually arrested for breaking into his apartment after failing to make rent, as chronicled in a 2019 profile on Brashear by Dan Robson:

“The landlord had warned him that he’d take action. He wanted Brashear gone — and now he’d changed the locks.Brashear paced the halls for a solution and found the management office open. He snuck in and took a ring of keys hoping to find the master.He tried them all. None worked. He thought about running right through the door.Brashear stormed out of the apartment complex to the patio of the below-grade ground floor unit that he’d been told he had to leave. It was early enough on that June morning in 2019 that no one was around yet. He slammed his fist against a crack in the corner of the window to his bedroom, knocking out a large chunk of plexiglass. Brashear reached in, unlocked the window and pulled his 6-foot-3 frame through…Several hours later, Brashear heard pounding at the front door. He looked through the peephole and saw the officers waiting. He brushed off the table and stuffed his last packet of cocaine in his pocket and bolted out the patio door.Officers were waiting there, too.Brashear laid on the ground, was arrested and stuffed in the back of a cruiser. With his hands cuffed in front of him as he sat in the back seat, he snuck the packet of cocaine from his pocket and hid it in his mouth. He held it between his teeth while he was searched again at the station. He felt the powder seep through the chewed plastic. His heart raced. In a panic — and high enough to think it might work — Brashear spit out the packet when he thought the officers weren’t looking. They turned just as it landed in his hands.”

The arrest led Brashear to visit another rehabilitation centre in Quebec. It was supposed to be a one-month program, but he stayed for five. He had had a couple of run-ins with the law before, but nothing serious enough to result in a criminal conviction. He had successfully kicked his habit, but now he was forced to navigate the job market as a 47-year-old black man with a criminal record and little in the way of formal education. With that in mind, Brashear accepted a job offer from former teammate Pierre Sevigny, who owned a nearby Tim Hortons franchise.

It didn’t take long for the media to catch wind of Brashear’s new vocation, with the Montreal Gazette quickly publishing an article with a photo of him working the drive-thru window.

Most of the comments the story received from fans were kind and supportive of Brashear, but it was impossible to escape the judgmental tone of the coverage his new job was receiving. Most of the media attention was framed in the same way: once a millionaire player, Brashear’s drug abuse and financial problems ignited a dramatic fall from grace that forced him to take a menial low-paying job to make ends meet. The fact that Brashear was actually in the process of ascending from the rock bottom he was at a year earlier was seldom remarked upon.

Worse yet, when the National Post ran an article about Brashear, they used a photo of a different black former Habs player: Georges Laraque, who was quick to lambast the Post for their mistake, as well as for the perceived job-shaming. He would later stop by a nearby Tim Hortons in full uniform and pose for a photo op in solidarity with Brashear.

Message for @nationalpost:There’s no such thing as a stupid job, there’s only stupid people. Every trade has value and requires qualities in the worker. Il n’y a pas de sot métier, il n’y a que de sottes gens. Tout métier à une valeur et requiert des qualités chez le travailleur! pic.twitter.com/7yewAu6sSc

— Georges Laraque (@GeorgesLaraque) October 21, 2019

Brashear handled the situation with grace and humility, expressing an immense sense of pride at his newfound health and ability to provide for himself: “I am proud to be a father to my children, whom I love, to take care of myself, to have a job that’s fun, that doesn’t necessarily pay very well, but that provides a roof, food on the table and joy for my family and myself, and, most of all, peace of mind.”

Donald’s time as a drive-thru clerk ended up being short-lived, anyway. By early 2020, he was working as a peer-to-peer counsellor for Portage Quebec, a rehabilitation program that focuses on developing self-esteem for people recovering from drug abuse by helping residents “work to identify the cause of their problems, develop skills that will help them cope with them, and implement strategies to address them without using drugs.”

As a member of the Flyers, community work had been a central part of his life. He worked closely with kids from Florence Klemmer House, a pre-adoption group home in New Jersey where residents undergo therapy for issues around loss and abandonment. One story in the Philadelphia Daily News recalled how Donald took a group of children pumpkin-hunting near Halloween and consoled a boy who was struggling with the absence of his mother.

He’s come full circle in his work with Portage, helping adults who have struggled with similar issues, and who often come from the same type of troubled background he did.

On the ice, he was most recently seen running a hockey clinic in partnership with the Flyers for a group of children in the community, the majority of whom are black.

Off the ice, he’s continued his work with Portage, where he’s drawn on his struggles to help others who are recovering from addiction: “At the end of my career, I quickly hit rock bottom. I had nothing left. No money, no friends, no home, nothing. There was only me, living in darkness and with a deep sense of shame. Until, one day, the light came back into my life. My spirituality helped me bounce back. I had the courage and humility to ask for and accept help. Now, my inner strength is what I am most proud of.”

When taken in its entirety, Brashear’s story is one of the most compelling and inspiring in NHL history. On and off the ice, he’s struggled against adversity again and again; surviving abuse, assault, addiction, and poverty while also amassing one of the most impressive careers playing one of the most difficult roles in a sport that produced only a handful of black players in its century-long existence.

It’s a story that not nearly enough people know, and that deserves to be highlighted as the sport of hockey works to shine a light on its black history and also to welcome new fans into the game.

The Canucks could potentially play a huge role in sharing his inspiring story by honouring him next year during Black History Month with more than just a passing mention in a pre-game video.

If the team is really serious about acknowledging the contributions of the league’s black players, it’s hard to imagine a better way to start than giving Brash one last moment in the spotlight.