With the news that Ilya Mikheyev is being shut down for the rest of the season, fans are rightfully wondering why the big free-agent acquisition was even playing on a torn anterior cruciate ligament. Some were quick to dub it another black eye on the Canucks’ medical staff, which has seen plenty of flak for how they handled Tanner Pearson’s hand injury and Thatcher Demko’s constantly changing timeline just this season.

The question still remains — how did Mikheyev play through a grade 2 ACL tear, one that was nearly a grade 3 full separation? It doesn’t seem logical for a player that thrives off of speed to risk damaging his knee further, in addition to the whole structural damage aspect to it. This is where things get interesting, and the answer might not be what you expect.

Anatomy and Function

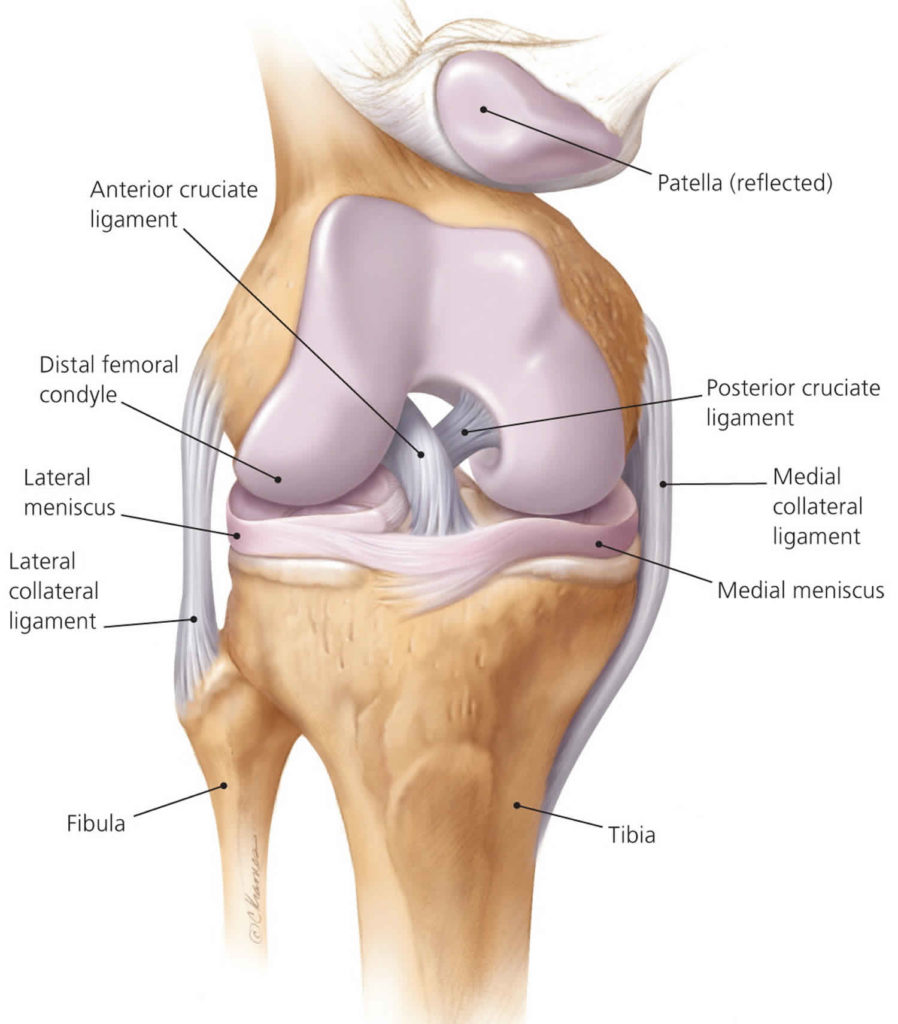

It’s first important to establish the function of the ACL with a bit of anatomy background. In the knee, there are four key ligaments. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) are dense connective tissue that link the femur and tibia together, running in a cross with each other. On the inside of your knee lies the medial collateral ligament (MCL), and on the outside is the lateral collateral ligament (LCL).

Together, the four ligaments combine to help stabilize the knee joint through the wide variety of movements that a person engages in throughout their daily lives. They do everything from absorbing shock to preventing the knee from twisting in unnatural motions. As such, they also happen to be prone to injury, especially in sports where abnormal loads are placed on the knee (depending on the sport) in practice and competition.

Focusing on the ACL, its function is to prevent excessive anterior translation of the tibia, that is, the movement of the tibia bone forwards. The ACL restricts the bone from shifting excessively forwards, while also aiding in restricting tibial rotation medially and laterally. Together with the PCL, it helps guide the centre of rotation in the knee, which becomes a key part of the biomechanics of how the joint moves.

Sounds pretty important

That’s because it is. The ACL’s structural role plays an important part in the explosive movements of any athlete, allowing for sudden changes in direction and sudden stops. Usually, an ACL tear is accompanied by menisci issues (the cartilage that allows the knee to bend) over 50% of the time, thanks to the role of the ligament in helping reduce the impact load.

But if that’s the case, how (and why) did Mikheyev play four months of NHL hockey on it?

Even with an ACL tear, most daily functions can be performed such as walking or a light jog for a non-elite athletic population. Weight-bearing isn’t too much of an issue depending on the severity of the tear. Going back to the paragraph before, it’s true that the ACL plays an important role in changes of directions, sudden stops, and sudden starts. However, this is the case when running on land. Hockey is played on ice.

The biomechanics of skating are different than the biomechanics of running. Skating relies on the edges of blades to generate power while at the same time maintaining balance. It’s a different motor pattern in comparison to running, where a predictable surface is in contact with a much larger surface area of the foot. As such, there’s a lot more work that needs to be done by the hips when skating relative to running, and by extension making the knee not as important as it would be if the activity was running. Therefore, the ACL just happens to be not as critical to the kinetic chain as it would be in a basketball player versus a hockey player.

The movements that the ACL aids in also aren’t as dramatically involved in skating. According to a 2015 study done at the University of Calgary, greater plantar-flexor muscle activity and hip extension were evident during acceleration strides, while steady-state strides exhibited greater knee extensor activity and hip abduction range (Buckeridge et al., 2015). In general, the ACL usually is more involved with flexion of the knee, with strength loss in flexion associated with reconstructive surgery of the ligament. Since most of the muscle groups engaged are extensors, chances are the ACL isn’t as involved in the skating stride.

What’s interesting is that the evidence of ACL damage is clear with hindsight. Cam Charron of the Athletic had posted a video remarking how slow he found Mikheyev — or rather, slower than he was last season. For most players at the age of 28, their footspeed shouldn’t drop off.

Mikheyev mentioned lacking “power” in his stride, which lines up with an ACL tear. Out of all of skating, the closest movement sequence that resembles running would be the initial strides. All season, there have been comments that his strides haven’t looked right, and this could potentially have been a clue. Because the first couple of strides are similar to running, chances are that Mikheyev’s knee wasn’t able to generate as much force as it did previously, thus making his acceleration that much longer. Of course, it was hard to notice — Vancouver fans aren’t very used to speedy players in the last couple of years, and so there wasn’t much of a benchmark to compare his pace to.

Alright, so why was he allowed to play?

On top of the previous points of the knee not being as critical to skating as it is to running, the ACL specifically, with proper consultation and evaluation, a tear like Mikheyev’s can realistically be managed through a season. The strongest ligament in the knee is actually the PCL, while the MCL and LCL aid in the medial and lateral stability of the knee respectively. In theory, only one movement’s support is affected through injury, and it just so happens to be movements that aren’t essential to skating.

Depending on the rupture too, it could have been a relatively stable knee that was left intact. For instance, if the rupture was of the anteromedial bundle of the ACL, it would cause anterolateral instability with an increase in anterior translation in flexion, which was already a given, while there would only be a minimal increase in hyperextension and rotational instability.

As such, the main thing here would be to brace the knee, which is what I’m hypothesizing the Canucks had been doing all season for Mikheyev. With a knee brace or prophylactic taping (or both), it would provide an external source of stability that helps reinforce the point of weakness. Obviously, it wouldn’t be as good as surgical intervention, where the ACL can be fully repaired, but the rehab and conditioning that will come after is very costly in time.

This is only a stopgap measure though. As time progresses, as more load is consistently placed on an injured knee without an ACL, other issues will start appearing. The aforementioned meniscus issues might surface, the other knee might see an increase in the risk of injury, the ankle or hip gives way from overcompensation. Sooner or later, Mikheyev would need to have been shut down for surgery. But playing him with a torn ACL wasn’t exactly a misstep.

There is rightful concern that playing on a torn ACL would make it worse. Because of the loss of stability, other ligaments and structures in the knees would be stressed more so than usual, which increases the risk of injury. However, this is only without proper support. It is possible to increase the stability of the knee through proprioceptive means, such as a brace like mentioned before. On top of that, since skating does stress the knee less than running, with adequate support underneath a shin pad, in theory, the risk of further injury can be minimized through proper care, management, and support.

At the end of the day, only the athlete can make the decision whether or not to risk playing on a damaged knee. Canucks fans might remember how Antoine Roussel never looked the same after getting his ACL repaired. But with Mikheyev, it’s impressive how well he performed despite everything, and how his speed was still incredibly quick. With the Canucks far outside playoff contention, it only makes sense to shut him down for the year, get him under the knife, and have him fully ready and healthy to go at next year’s training camp.