Beware of What Zone Starts are Telling You, Part I: Coaches’ Deployment

By Jeremy Davis

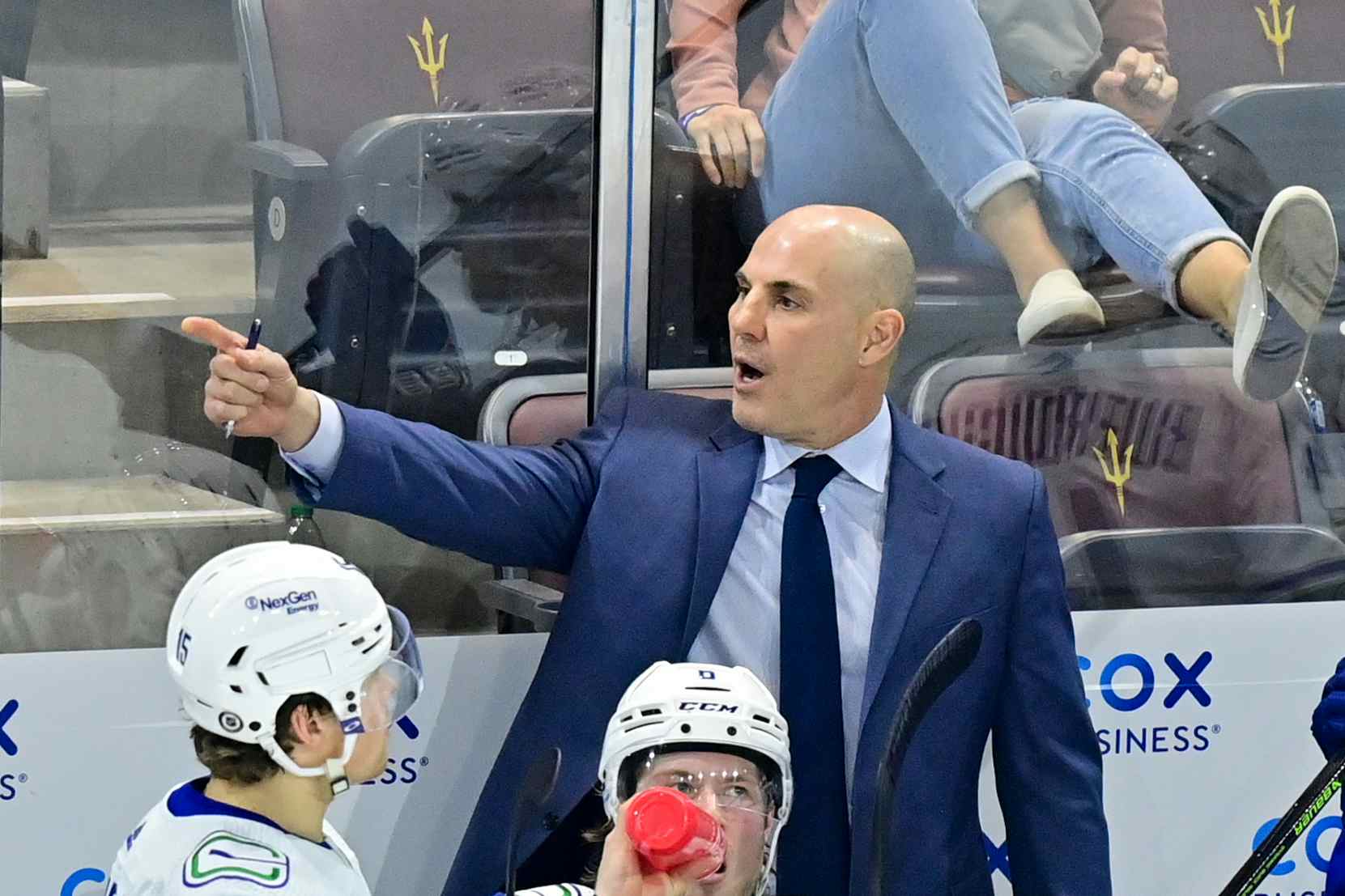

7 years agoIt’s early in the 2016-17 NHL season, but it’s never too early for Canucks fans to start complaining about player deployment! This season has already seen its fair share of head scratching decisions when it comes to who plays when (and with who), and it’s not going to get any easier on Willie Desjardins and his crew if the team keeps on losing.

NHL coaches can’t slip much past the general public these days, what with the ease of access to massive amounts of data, and deployment is no different. One of the most commonly cited events are zone starts, purported to be both an indication of how coaches deploy players and context to explain high or low shot differentials. As it turns out, both of these connections may be greatly exaggerated, meaning these numbers might not be telling you what you think they are.

A note on terminology: in an effort to use terms that better encompass the events that they are meant to describe, I will be using terms in this article that don’t necessarily match those most commonly used. For example, as a disciple of Micah Blake McCurdy’s methods, shots* (with an asterisk to remind you when reporting actual numbers) will refer to what are commonly called shot attempts – that is, every time a puck is shot at the net, regardless of whether it hits or misses. “Unblocked shots” will replace unblocked shot attempts (also known as Fenwick), missed shots will replace missed shot attempts, and shots-on-goal will replace shots.

Furthermore, I’ll be endeavoring to resist using the term “possession” when referring to on-ice shot metrics, preferring to use “shot shares”, “shot differentials”, “shot ratios” and the like. While on-ice shot metrics have long been a proxy for possession, research comparing the two has found that not only are they less correlated than we’d assume them to be, but that shot metrics are actually better indicators of future goals and wins – in other words, they are more meaningful than pure puck possession.

Please bear with me as I try to join the movement to making fancy stat terms more intuitive.

Surging in Popularity

Zone starts seem to be the talk of the town this season. All over twitter you will see them used in mainly two ways: to talk about the way coaches deploy their players, and to imply that player’s shot metrics are more impressive when their offensive zone starts are low.

Here’s a selection of tweets on the subject – I’ve left names and handles out, because the purpose of this article certainly isn’t to ridicule anyone who has been using them in this manner, but simply to bring some awareness to the statistical validity of a commonly referenced statistic.

In Part I of this little series, we’ll discuss why zone starts are affected by more than just coach’s decisions, and other factors that limit the coach’s ability to have complete influence over them.

OZS% versus ZSR

Something to take note of is that there are differences in terminology here and there, and they can make a major difference. When people want to express zone starts by a percentage, they’re often thinking of offensive zone starts compared to defensive zone starts. However, they often report it as OZS%, or offensive zone start percentage, which isn’t actually the same thing.

OZS% is the percentage of all zone starts (faceoffs) that occur in the offensive zone – this means that you are including neutral zone faceoffs in the denominator. If your goal is to compare offensive zone starts to defensive zone starts, then your missing your target here. What you’re actually looking for is ZSR, or Zone Start Ratio – this is the ratio of offensive zone starts to offensive and defensive zone starts, but not neutral zone starts. This number more accurately portrays the relationship that is intended.

There’s a fairly simple explanation for this misunderstanding – the website HockeyStats.ca (which, don’t get me wrong, is a wonderful and useful site) reports zone percentages in its on-ice tables under the heading OZS%, clearly referring to the offensive to defensive relationship. In addition, NaturalStatTrick.com, another great website for in-game shot metrics, reports Offensive Zone Faceoff %, again omitting neutral zone faceoffs.

This is only going to lead to confusion when heading to an aggregating website like Corsica.hockey, where both OZS% and ZSR are listed – though using the intuitive labels: OZS% includes all starts, while ZSR omits neutral zone starts. ZSR is the more important metric. I would assume that most people referencing zone start numbers are doing so in the spirit of ZSR, so that’s the label that should be used, rather than OZS%.

Zone Starts versus Shift Starts

Now that we’ve established why ZSR is important, I’m going to tell you why its rife with problems.

The first thing that we have to be aware of here is that zone starts and shift starts are not he same thing. This is highly intuitive if you define your terminology succinctly. When I refer to shift starts, I’m referring to the time a player come over the boards and enters the rink. This could be for a faceoff in the offensive, defensive, or neutral zone, or it could be an on-the-fly change.

On-the-fly shift starts are often neglected when we talk about deployment, which is silly when you think about it. They’re not only important, they’re far and away the most common type of shift start. Matt Cane found that roughly 60 percent of shifts start on the fly, which drastically reduces the impact of each shift that starts via a faceoff.

While it’s obvious that when we include on-the-fly metrics our measures should decrease, the actual number of shifts that start on-the-fly (and hence don’t really offer any zone-start advantage) is quite staggering. An average player should expect roughly 60% of his shifts to start on-the-fly, with the remaining 40% divided up between the offensive, defensive and (most commonly) neutral zones. While our traditional metrics have players starting approximately 30% of their shifts in the offensive or defensive zones, when we use True Zone Starts we see that the number drops down to about 10-12%.

Here you can see the differences between what Cane deemed traditional zone starts (all faceoffs) and True Zone Starts (shift starts only).

Notice that it isn’t only the percentages that are dropping, but the standard deviations as well. What this indicates is that there is far less variability between players than was previously indicated. Coaches aren’t actually making nearly as many decisions between the offensive and the defensive zones. Single digit differences between OZ and DZ starts can be magnified by the fact that an offensive zone shift start is highly likely to be followed by another offensive zone faceoff within the same shift, and the same can be said for defensive zone shift starts.

Matt Cane further determined that the correlations between zone starts and shift starts are woefully low (for something that used to be considered roughly the same thing), which only leads to the notion that using ZSR as an indicator of coaching deployment needs to be viewed as a mere approximation.

Furthermore, this becomes a bit of a sample size issue. We view ZSR as a relation between only faceoffs in the offensive and defensive zones, when deployment in these zones only account for 20-22 percent of shift starts (which are then compounded by the rate of multiple faceoffs in the same zone in the same shift). The coach has to decide to send out players for the other 78-80 percent of shift starts, having no idea where those shifts will end. This lack of control ties in with our next topic.

Deployment Freedom

The difference between zone starts and shifts starts is clear cut, but the ability of the coach to turn one into the other is not so clear. For instance, I’m suggesting that shift starts are more important than zone starts, but isn’t it true that a coach has the ability to re-deploy his lines at each faceoff, even if the shift has only just begun?

As it turns out though, this isn’t something that coaches seem to be predisposed to doing.

Micah Blake McCurdy, following in the footsteps of Cane’s work, discussed among other things the degree to which coaches are truly free to deploy players at each individual faceoff:

Coaches have as much free choice when they choose who will start the next shift for on-the-fly shifts as they do for faceoffs, so they are correctly thought of as part of a players deployment. On the other hand, faceoffs which occur in the middle of shifts should not generally be thought of as “re-deployments” of the people who remain on the ice. For the majority of such faceoffs the coaches do not have the free choice of all possible replacements, since the previous line has only very recently come off the ice. Furthermore, the very-close-to-normal distribution of overall weighted shift lengths strongly suggests that coaches’ aggregated preferences are biased towards keeping shift lengths around 45 seconds; if they were (collectively) aggressively seeking specific matchups with quick changes early in shifts, we would see a skew towards short lengths.

In other words, the obsession with 45 second shift lengths often prevents coaches from swapping lines at a stoppage ten seconds into a shift just because the play stopped in the offensive zone. Additionally, players that have just come off the ice ten seconds prior wouldn’t be ready to go out again, thus limiting the coach’s actual degree of freedom to deploy the line of his choosing.

Another factor that limits the coach’s ability to control deployment is that he doesn’t control where the shift actually starts – the players do (Corsica also list ZFR, or Zone Finish Ratio, but that’s for another time). If the team as a whole is getting only two thirds as many offensive faceoffs as defensive faceoffs, it becomes trickier for anyone on the team to have a positive ZSR, let alone have multiple lines doing so.

The Canucks are performing about average in this category, with a team ZSR of 49.3 in the month of October, meaning they are very slightly taking more defensive faceoffs than offensive faceoffs.

Now if you were Ottawa, way up there in the right hand corner, it would be easy for the majority of your players to have a high volume of offensive zone starts.

When it comes to picking the players to deploy for an upcoming zone start though, there is an entirely separate situation where all lines are rested and the coach has the highest degree of freedom to send out the line that he perceives to be best suited to the particular zone – assuming he isn’t just tapping the just line in the rotation.

Post-TV Timeout Deployment

Post-TV timeout deployments may be the surest measure of coaching preference, with line matching being the only remaining consideration.

In the month of October, the Canucks played nine games. In each game, there are three periods, each of which has three TV timeouts, for a total of 81 TV timeouts altogether. 64 of these have been followed by 5-on-5 faceoffs, distributed in 19 offensive zone faceoffs, 19 neutral zone faceoffs, and 26 defensive zone faceoffs.

The following chart show how many 5-on-5 faceoff each Canuck was present for following TV timeouts in October (TVT denotes TV Timeouts, so TVTOZS is a TV Timeout Offensive Zone Start; %TVTOZS denotes the percentage of team TVTOZS that the player was on the ice for). The chart is sorted by offensive zone starts.

Note that while the Sedins and Loui Eriksson are near the top, the second line of Brandon Sutter, Markus Granlund and Jannik Hansen has nearly as many offensive zone starts following TV timeouts. Markus Granlund leads the team in neutral zone starts after TV timeouts, while Brandon Sutter leads all forwards in total starts after TV timeouts.

If you’re going to complain about the deployment of players, this is probably the ammunition to use to do so. The young combo of Bo Horvat and Sven Baertschi have been heavily geared towards defensive starts – although that might not be the worst thing… more on that in the future.

Summary

The takeaway from part one of this series is that the coach has less influence over zone start ratios than one might think. Of course there’s a conscious effort to get your best offensive players out on the ice for offensive draws more often than others, but this is quite difficult to do with more than one line at a time if your team is a 50/50 ZSR team.

Additionally, the actually amount of shift starts is quite small in each game, and a heavy portion of them are restricted in one way of another in terms of freedom of deployment. Random chance is occasionally going to prevent you from placing ideal players in ideal situations, and those are going to make up a decent ratio of the total shift starts.

TV timeouts carry the highest level of freedom of deployment, and thus may be the best indicators of coach’s choices.

In Part II, we’ll see how zone starts have strong effects on shot rates – and why that doesn’t really mean a whole lot in the long run.

Recent articles from Jeremy Davis