About That Authority You’re Appealing To…

By Jeremy Davis

6 years agoThe big news this week is obviously the re-signing of Canucks defenceman Erik Gudbranson. It’s everywhere, and you’d have to be actively ignoring all things Canuck-related to miss it (although no one would think less of you for it).

This news was such a massive deal that it’s only natural that everyone – from pro-analytics to anti-analytics, west coast to east coast, fan to blogger to national analyst – has an opinion on it. Everyone has a right to an opinion, and no one in this country in this day and age can prevent you from expressing it. That doesn’t necessarily mean that all opinions are of equal value though.

No, I’m not going to get into a statistics versus eye-test type of debate today; I’ve already gone far enough down that road. My interest today is not about those two methods of forming opinions, but a third option: basing opinions off of what someone else told you.

Because every Vancouver hockey fan seems to have an opinion on Gudbranson, there is no shortage of people available to give you their impression of him. There is a natural inclination, however, to listen to those people who are in positions of power in a relevant area.

Around here, that typically means the management staff of the Canucks or some other NHL team. These are a group of people who have been involved in hockey for their entire lives. They played the game; they were in the dressing rooms; they battled out there on the ice. They are real, authentic Hockey Men. Therefore, they have an understanding of what it takes to win in this league, making them ideal candidates to assemble the right group of players and subsequently deploy them in an ideal fashion.

If you are one of those people that assumes that hockey executives always know what they are doing because it’s their job to know, you are engaging in a logical fallacy called the appeal to authority (or alternatively, argument from authority). This fallacy can be defined as “an error in reasoning which occurs when someone adopts a position because that position is affirmed by a person they believe to be an authority.”

This fallacy is similar to, but distinct from, another logical fallacy than has been brought up: an appeal to non-authority, in which the opinion of an authority figure from a different discipline is invoked. For example, assuming that the opinion of a Nobel Prize-winning physicist is correct when discussing nutrition. This fallacy is also prevalent, but isn’t relevant in this case.

What we’re concerned with instead is when the figure is an authority on the relevant subject matter. While this can in fact bolster their opinion, it cannot guarantee to correctness of it. To borrow from Carl Sagan in the field of science, “One of the great commandments of science is ‘Mistrust arguments from authority.’ Authorities must prove their contentions like everybody else.”

The assumption at the core of this issue is that being a general manager is an authority in hockey, their opinions are automatically correct. There are some serious issues with this assumption. First and foremost, it assumes that experience in the hockey world provides one with a level of expertise in all areas connected to hockey, including management. There’s a pretty big leap of logic required to believe that playing a sport makes you automatically good at skills like business management, asset evaluation, and market analysis.

Unfortunately, that doesn’t stop fans and even media from countering criticism with responses like “he knows better because he’s played the game and been around it his whole life!” Worse yet is the throwaway line from NHL insiders that “league source X appreciates player Z, so why don’t you?”. I’m sure he’s not the only one, but I’ve caught TSN’s Pierre LeBrun dropping this one a couple of times concerning Gudbranson lately, most recently on Tuesday following the extension.

“I know what the analytics community says, they make some good points as well,” LeBrun told TSN’s Mike Halford and Jason Brough. “But all I can tell you is this. The first reaction I got from a rival GM yesterday when McKenzie put out the first parameters, was that he would do that in a heartbeat. And this is a playoff team.”

LeBrun very obviously expects this bit of information to be of great import and delivers it in a way as if it settles the matter. As if, because a general manager of a playoff team would pay Gudbranson $12-million, that automatically makes it a wise move. Case closed.

Then there’s Mark Spector’s infamous, ill-advised, and widely mocked suggestion to “poll 200 hockey men” to get a concrete answer on a subject.

Now, I don’t always agree with the people that reject stats outright in favour of eye tests and instinct, but I can at least respect that they’re formulating their own opinion. Even if I don’t place the same value on specific traits, at least those people can defend their view using particular examples.

What I have trouble respecting is opinions that are formed solely by other people’s opinions: not just using an argument from an authority to support your opinion, but as the very basis of it. I believe that no idea should be above scrutiny, but before I get into that, I’d like to discuss why the opinions of hockey general managers, in particular, should be subject to reasonable scrutiny.

Hockey and Higher Education

It is traditional in hockey (and sometimes in other sports) to draw on the pool of former professional players when filling out a staff of coaches and executives. One of the common themes that comes as a result of this process is that the executives avoid going to post-secondary school. Instead, they jump from junior hockey to professional hockey at a young age and then dive directly into a scouting or managerial role immediately after their playing careers come to an end.

Is it possible to learn a variety of business skills over years or even decades on the job? Absolutely it is. Does that guarantee that they’re objectively qualified to run a business worth nearly three-quarters of a billion dollars? Colour me skeptical.

No one can be faulted for taking a lucrative job offer in a field in which he has spent his entire life playing or working, so it would seem a bit unfair to criticize the men for taking the jobs in the first place rather than returning to school. Besides, this is par for the course in sports, or at least in professional hockey.

Hockey, more than other of the other major North American professional sports that comprise The Big Four, keeps a remarkably tight in-group when it comes to management. According to some digging done by Jason Paul, the NHL easily has the highest proportion of former players among their league’s set of general managers.

While Major League Baseball has just one former MLB player in a GM seat (Seattle’s Jerry Dipoto) and the NBA has eight, the NHL’s collective general managers contain a whopping 19 former NHL players. (Note: I wound up with four fewer former NHL players-turned GM than Jason did, although three more had AHL experience.) Further, as Paul points out, the remaining general managers still have pretty strong ties to professional hockey.

| Team | General manager | Highest Level of Hockey | Team | General manager | Highest Level of Hockey |

| Anaheim Ducks | Bob Murray | NHL | Nashville Predators | David Poile | AHL |

| Arizona Coyotes | John Chayka | BCHL | New Jersey Devils | Ray Shero | NCAA |

| Boston Bruins | Don Sweeney | NHL | New York Islanders | Garth Snow | NHL |

| Buffalo Sabres | Jason Botterill | NHL | New York Rangers | Jeff Gorton | |

| Calgary Flames | Brad Treliving | AHL | Ottawa Senators | Pierre Dorion | |

| Carolina Hurricanes | Ron Francis | NHL | Philadelphia Flyers | Ron Hextall | NHL |

| Chicago Blackhawks | Stan Bowman | Pittsburgh Penguins | Jim Rutherford | NHL | |

| Colorado Avalanche | Joe Sakic | NHL | San Jose Sharks | Doug Wilson | NHL |

| Columbus Blue Jackets | Jarmo Kekalainen | NHL | St. Louis Blues | Doug Armstrong | |

| Dallas Stars | Jim Nill | NHL | Tampa Bay Lightning | Steve Yzerman | NHL |

| Detroit Red Wings | Ken Holland | NHL | Toronto Maple Leafs | Lou Lamoriello | NCAA |

| Edmonton Oilers | Peter Chiarelli | NCAA | Vancouver Canucks | Jim Benning | NHL |

| Florida Panthers | Dale Tallon | NHL | Vegas Golden Knights | George McPhee | NHL |

| Los Angeles Kings | Rob Blake | NHL | Washington Capitals | Brian MacLellan | NHL |

| Minnesota Wild | Chuck Fletcher | Winnipeg Jets | Kevin Cheveldayoff | AHL | |

| Montreal Canadiens | Marc Bergevin | NHL |

Of the 12 that never played an NHL game, three played in the American League, and three more in the NCAA. John Chayka, now the strawman for what happens when analytics take a choke hold on a team, was once a promising player who made it to the BCHL before injuries forced him to change his plans.

That leaves five GM’s without any real competitive hockey experience, but four of them introduce another common theme: nepotism in hockey. Stan Bowman is the son of Scotty Bowman, the NHL’s greatest ever coach; Chuck Fletcher is the son of former NHL GM Cliff Fletcher; Doug Armstrong is the son of a Hall of Fame NHL linesman; and Pierre Dorion is the son of a former head scout of the Maple Leafs.

New York’s Jeff Gorton is truly the odd man out: he went to university, then received a master’s degree in sports management, and has been working in the NHL since 1992. Seriously, the odd man out is the one with a master’s degree in sports management.

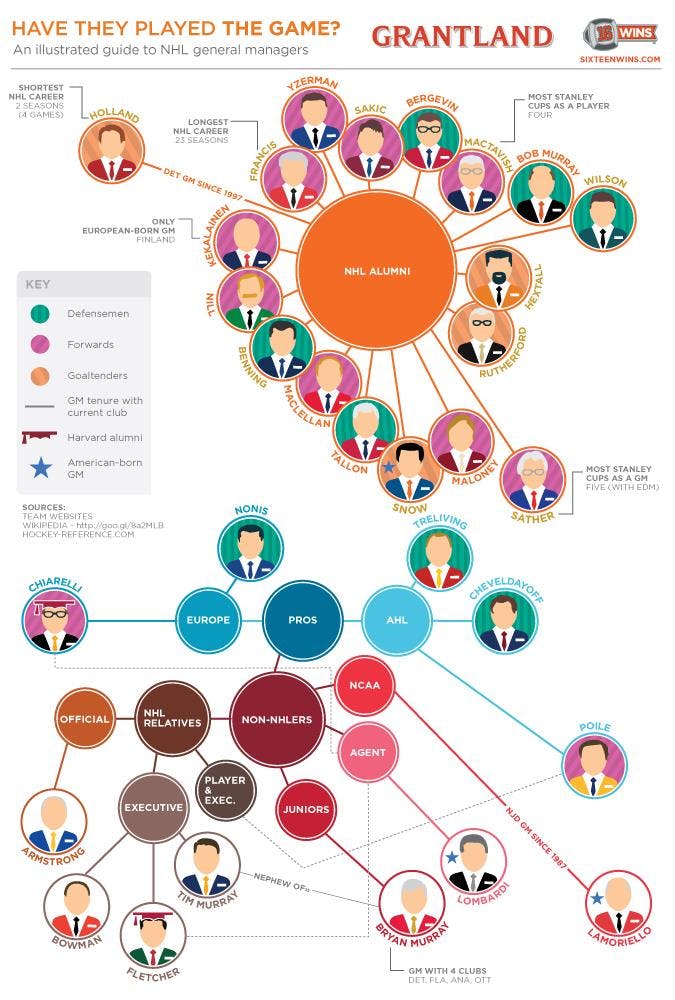

This research reminded me of an article by Sean McIndoe (a.k.a. DownGoesBrown) on Grantland a few years ago, and although the infographic below is now out of date, most of the overarching themes remain the system: the big bosses in hockey have deep roots in that sport.

Here’s where it gets even stranger, at least from my perspective, and ties back into what we were initially discussing: higher education. 26 of the 30 general managers in the NBA attended post-secondary school. In the MLB, a clean 30 out of 30 went to college for some period of time. Jason Paul didn’t have complete data on the NHL here, but from what I can gather, 15 of the 31 NHL GM’s have some college or university experience. Most of those are players who played NCAA hockey, with a couple of outsiders (John Chayka and Jeff Gorton) who studied sans competitive hockey. There are even a few with masters degrees, while Chiarelli earned himself a law degree.

The NHL has always been a bit slower to adapt to the education route compared to the other major spots. Consider this quote from George Kingston, the first coach of the San Jose Sharks and one of the founders of the NHL Coaches Association, on the evolution of coaching in hockey in a long-form article from Eric Duhatschek at the Globe and Mail last year:

What hockey in Canada missed in its evolution was what baseball, basketball and football had – the education route. All three of those other sports were played in the schools. Hockey, in the 1950s, was played outside of the schools. The other sports had coaches and leaders who were also teachers and wrote books about their sports. That was not part of the tradition of hockey.

Even though nearly a third of NHL players now come from the NCAA, that route has long been the primary non-professional league in other sports, versus the likes of the CHL in hockey, which not only isn’t coupled with education but actively prevents admission to the NCAA. And while the CHL is now doing better by its players with respect to education, that wasn’t the case 20 or 30 years ago, when some of these general managers were passing through: a time when coaches or managers might be as likely as not to encourage players to drop out of school to more effectively focus on hockey.

Again, I should stress that the point here isn’t to shame any of the current GM’s who didn’t have the opportunity of higher education, but merely to point out that a good portion of these people may lack training in areas that would be fundamental requirements in any other type of business. Does this mean that they have no idea what they’re doing? Absolutely not. But it also provides substantial evidence that they aren’t infallible.

Management that got where they are because they played the game rather than because they received professional education are always going to be predisposed to listening to their instincts and anecdotal opinions of like-minded allies over the reasoned conclusions of outsiders. It’s why hockey management groups often seem to be employing group-think strategies that appear as echo chambers, directly in contravention with what you see in the business world, where opposition fosters growth and development.

Sports management is never going to be functional without people who are intimately familiar with the sport, and there is always going to be a need for front office staff that can relate directly with the players on the ice. But the time may soon be coming when the NHL as an entity realizes that they don’t need liaisons at the top of the pyramid, where there is so much more going on that just understanding the game. The introduction of programs like the Business of Hockey Institute at Athabasca University, home of the world’s first hockey specific MBA program, could open doors for academic and business minded individuals to rise through the ranks of NHL offices in the near future.

A Healthy Dose of Skepticism

So, my advice to the likes of Lebrun is this: come up with your own conclusions on players. I understand that insiders traffic in the comments of authority figures, but there is a massive difference in usefulness between “what are team executives going to do?” and “what do team executives think of this individual player?”. I don’t know the quality of the source from which the information is coming from (nor would I expect to have it revealed, I know how the game works). Is this source the scout that found Jamie Benn in the fifth round? Or is he one of the scouts responsible for the Canucks’ 2007 draft class that amounted to exactly zero NHL games played.

And should it even matter whose opinion it was? Even those with immaculate records are capable of overvaluing or undervaluing players, traits, et cetera. I come from a discipline where you’re taught never to take what you hear or read at face value. That’s why, even though a textbook might be written by a man or woman with a PhD, every assertion inside the book is given a citation to peer-reviewed research. No authority is so great that their opinion should go entirely unscrutinized, even if that opinion is within their field of expertise.

So no, at no point will I ever be satisfied with an appeal to the authority of Hockey Men™. Never will I immediately accept that NHL GM’s know better than me on a particular subject because they get paid to do it, and I’m just a lowly blogger. Do they know more about the intricacies of the sport and the psychology of the players than I do? Most likely. But that won’t stop me from asking questions and levying criticisms when I see fit. Frankly, any executive that is unwilling or incapable of defending their position shouldn’t be trusted. And to his credit, Vancouver’s general manager Jim Benning has never, to my knowledge, taken offence to being asked to justify his actions (even if we aren’t always satisfied with his defence), so it mystifies me that some fans and some media members get their backs up when a GM’s moves are criticized.

In the end, the results will speak for themselves, and all of us will either be proven wrong or right. In the meantime, I strongly advise that everyone think for themselves, come to your own conclusions, enjoy the public discourse, and stop using the opinions of authority figures as conclusive evidence.

Editor’s Note: This article was edited after publication to focus less on Jim Benning and more on hockey management and implicit trust therein in general. (11/11/18)

Recent articles from Jeremy Davis